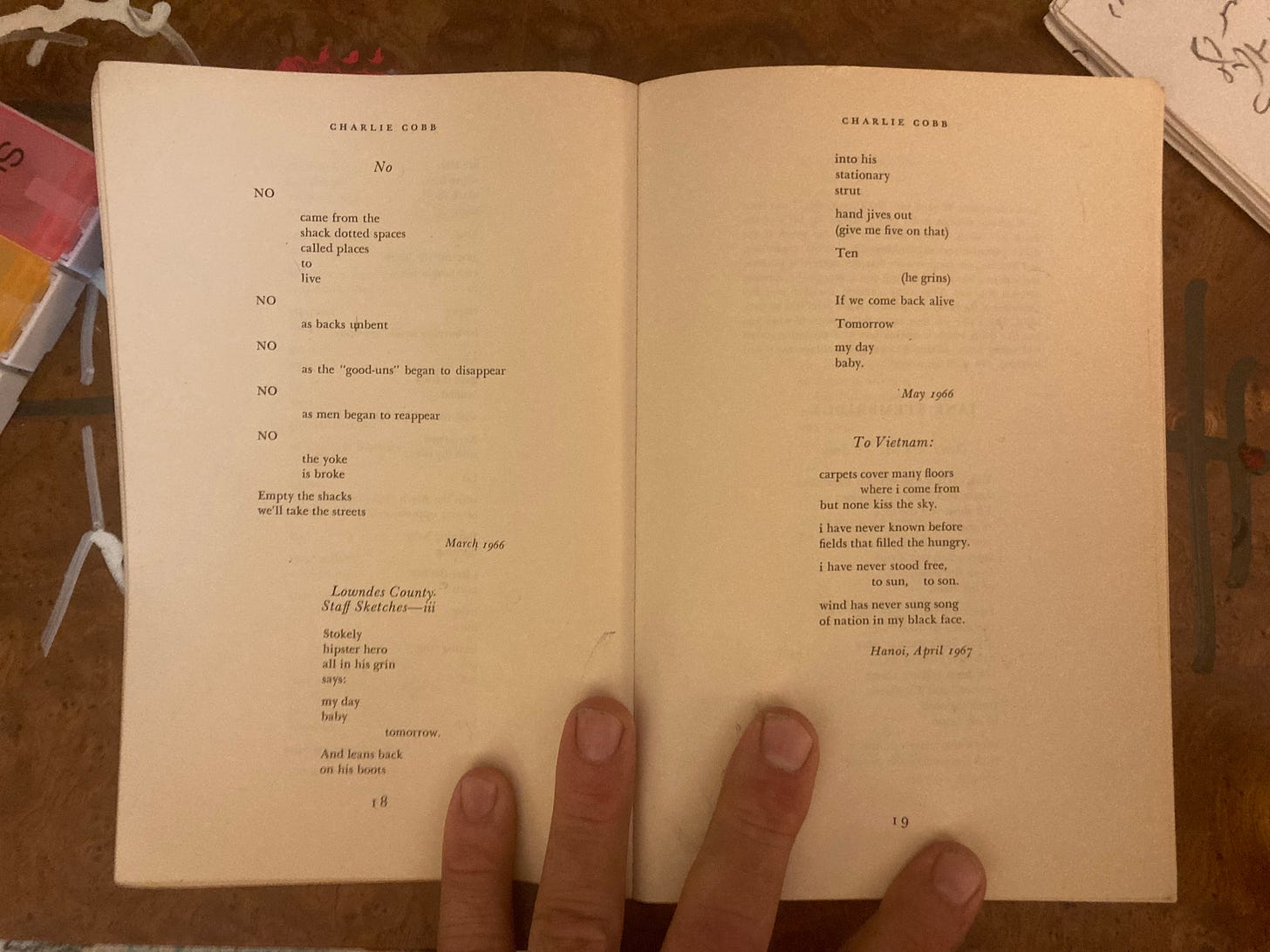

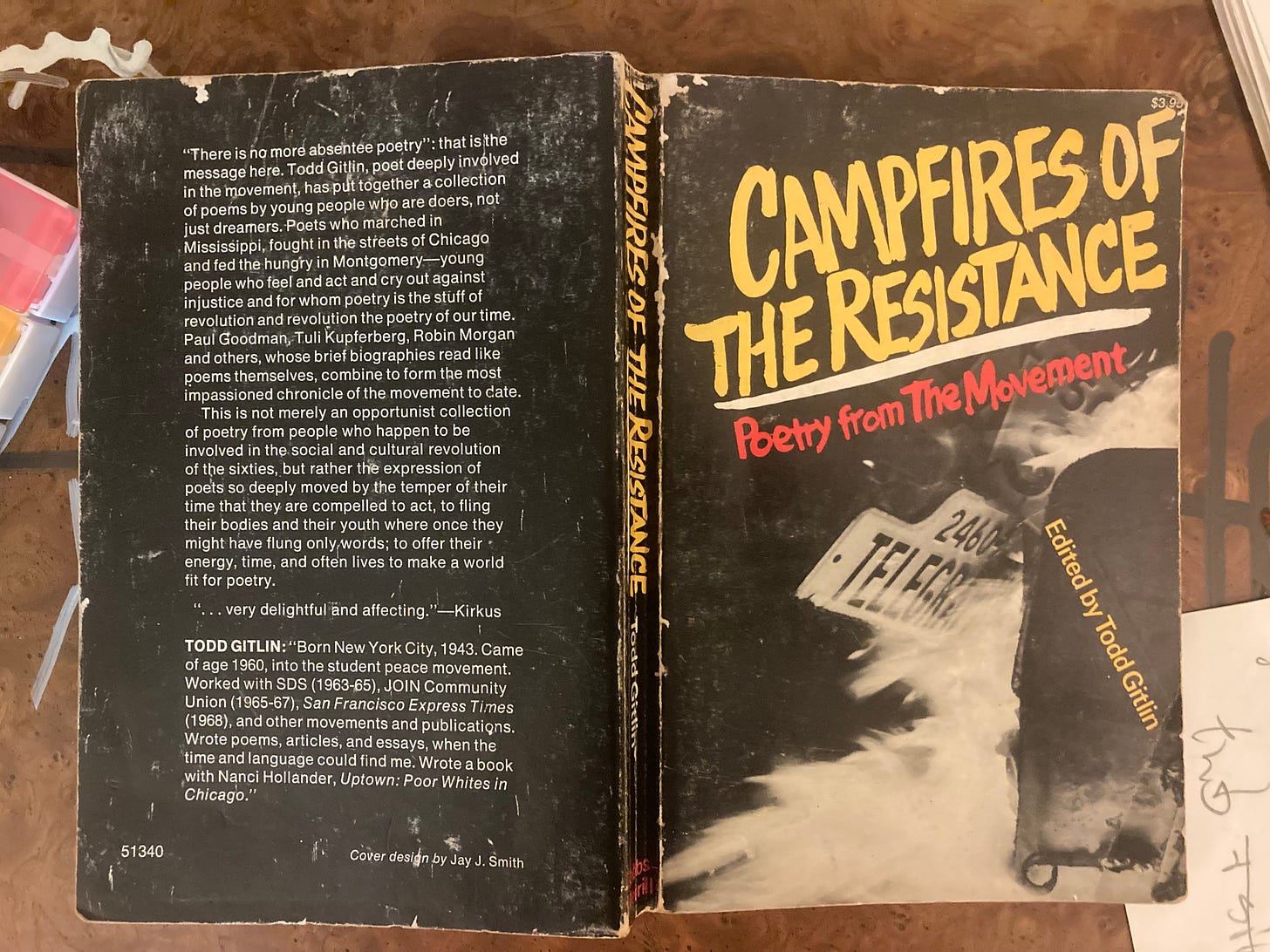

To Vietnam: (i) and In the furrows of the world (i) and Campfires of the Resistance (ii)

from revolutionary, poet, and journalist Charlie Cobb and editor Todd Gitlin

I met my friend Joe once only and didn’t expect to meet him again. I was in love with one of his patients. The doctor was going to die soon.

There was nothing to be done about it. He was not taking heroic measures. He had once, 50 years before, in Albany, Georgia.

He rallied to the cause of the 4 of every 10 adult citizens there denied civil rights. If you follow this kind of thing, registering voters at Albany was like landing at Normandy or Tarawa, with more black men and abundant women.

I don’t ask old militants about their war because they will answer some question they think you are asking, in words they expect you already have heard. Instead we have some more authentic conversation about the weather.

Keep that up every now and then across the years of a lifetime and 1 day you 2 may connect over history. Or not. It’s not a big deal. Big deals are not a big deal.

The 1 chance Joe and I had to talk turned nonetheless to his revolution. We weren’t going to make friends, because death. I wasn’t going to chatter.

“What did you learn,” I asked him. “What did you learn at Albany, Georgia?”

“I learned,” he replied, with a Kermit the frog roll of his head between low shoulders, “I learned to ride at the back of the bus and be happy.”

Not what you expect to hear from a soldier of the freedom movement. Not something you already know what it means. It can mean something.

What do you make of this poem?

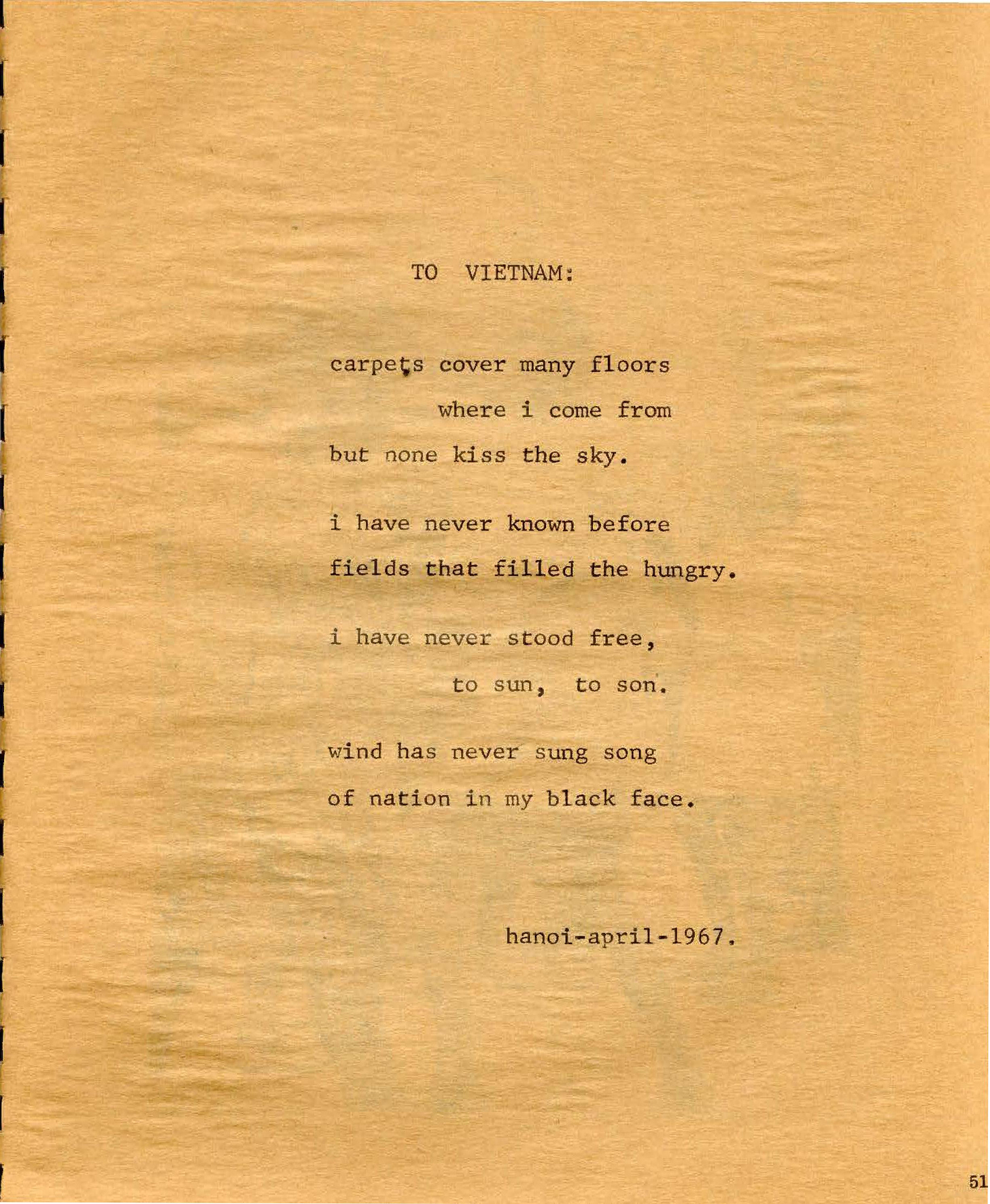

TO VIETNAM:

carpets cover many floors

where i come from

but none kiss the sky.

i have never known before

fields that filled the hungry.

i have never stood free,

to sun, to son.

wind has never sung song

of nation in my black face.

hanoi-april-1967

I can tell you some things about it. The title addresses the country of Viet Nam from Ha Noi where the dateline says the poet speaks in the month of April, 1967.

The International War Crimes Tribunal sent Charlie Cobb and Julius Lester of the cultural committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee there as a delegation of 2 members in spring that year. Julius recalled 30 years later to James W. Clinton that he marked Easter in Thanh Hoa province under naval shelling.

That holiday fell on March 26. Julius further remarked on attending 1 farewell banquet after another, 3 total, when cancelled flights delayed their exit for a week, twice. So, the poet and the singer traveled the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam over March and April, 1967.

The United States Air Force and the United States Navy were duking it out with DRVN air defenses. None of them make it into the poem. Neither does the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Junior, who gave his sermon Beyond Vietnam, the war, that April 4 at Riverside Church in New York City.

carpets cover many floors where I come from but none kiss the sky.

The Reverend Charles Earl and Martha Kendrick Cobb raised Junior, known as Charlie, in Springfield, Massachusetts. It was a prosperous farm town on rich bottomland of the Connecticut River.

So, yeah, plenty of carpets. None kissing the sky. I think we are to see the poet from New England gazing out over the green paddies of the Red River delta.

i have never known before fields that filled the hungry.

There must have been truck farms around Springfield. But the money crop there is tobacco, wrappers for the finest cigars of the cartoon rich.

Charlie is seeing fields without capitalism. He comes more directly from the fields of Mississippi. They do touch the sky as in Viet Nam, and somebody must grow some food, but the crop is cotton, a commodity you can’t eat.

So, yeah, I think I take his point.

i have never stood free, to sun, to son.

This point, not so much. One grandfather of the poet’s mother founded a free black town in Mississippi. He hired away the tenant of a neighbor who then led a mob to beat his business rival down with axe handles. Free men in a free market but also in free assembly for redress of grievances.

Charles, Senior, led a congregation in my own Puritan denomination that first settled my home town and native Connecticut and built our national college, Yale. He chaired our Congregationalist committee for civil rights in the long freedom movement of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in alliance with the Episcopalians, Friends, Methodists, and Presbyterians.

Junior in his turn served as field secretary for SNCC in Mississippi across 5 years when he made his mark authoring the proposal for Freedom Schools. I take Charlie in his poem to say that this preacher’s kid never before has stood free in the sun as he does in Ha Noi, watching the fields kiss the sky, free at last, for a moment, of duty to struggle for freedom.

I don’t know what the extra space in that sentence, carefully preserved from edition to edition, suggests.

to sun, to son. Is the second to, like the first, an element of an infinitive, of a nonce verb, to son from the noun son? Never before has the poet stood free to be a son?

Or is to in both cases a preposition? Or once a preposition and the other an infinitive?

What would any of that mean? For that matter what does it mean to use all lower case except in the title?

Why did some change to capitals and others not in the selection of the poem from its early publication at In the furrows of the world to Todd Gitlin’s reprint in Campfires of the Resistance? Does it mean those changes are important or that they are trivial?

wind has never sung song of nation in my black face.

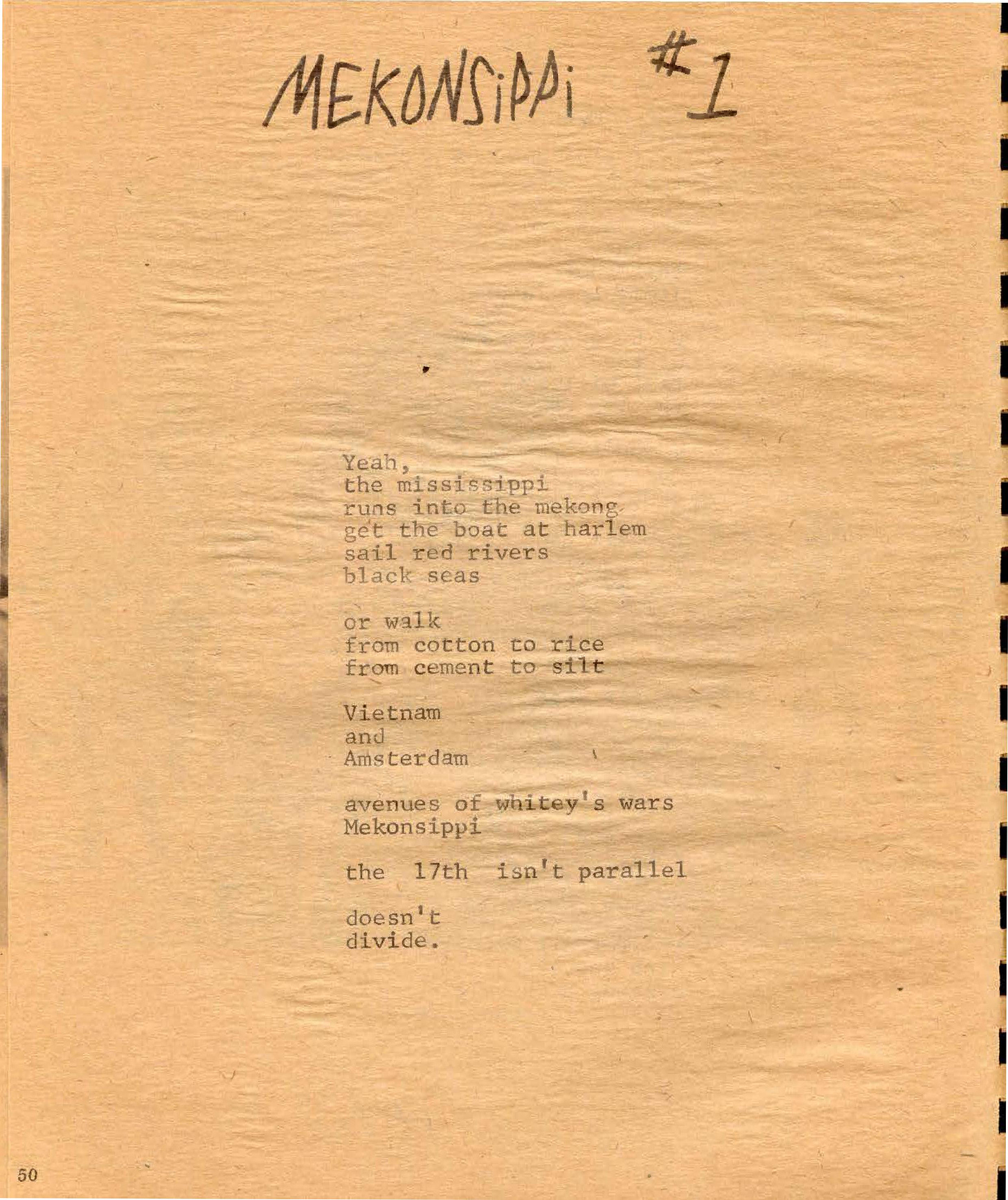

I think the whole poem dramatises and suggests that he is figuring things out. Look at the imaginary mash-up of notions in Mekonsippi #1 and the other verse on the previous pages in both books photographed.

To Vietnam: by contrast stands grounded. There the poet stands in the wind off the delta not yet singing song of nation in his black face. I feel sure he does not mean by black face the minstrel sense of blackface.

Oh. Charlie, the poet’s name, does not suggest to this native speaker either Charlie the boss man or Charlie the Vietnamese Communist.

But I don’t yet know what Charlie does mean. The poet didn’t know what he meant yet. Not only had he left Mississippi but SNCC had gone all-black and his close comrades turned from voter registration to televisionary claims of black power

while the other movement, to withdraw the United States of America from Viet Nam ground on with the war taking Lyndon Baines Johnson, the legislator and president of civil rights and his Great Society with it.

Charlie Cobb traveled on from Viet Nam to visit other nations. He came from teaching freedom through reading and the vote, stopped by Viet Nam, then went on to writing about Africa, and about how you might want to teach math to the oppressed. His most recent book, published here in Durham, explains how his non-violent insurgents in Mississippi all owned guns.

Đi một ngày đàng, học một sàng khôn. You can look it up if you don’t speak the language. What did you learn on the revolutionary road, I ask you.

What have you learned from reading the poem of a republican militant soldiering against Democratic rule dropped into the Viet Nam mobilized for freedom and independence under 1 party against the attack of the USA?

No rush. Some art requires life. All life requires art. Read at the back of the bus and be happy.

We introduced Todd Gitlin’s anthology Campfires of the Resistance in a previous Viet Nam letter on Will Inman’s poem Tonight in Washington . . . Ho Chi Minh:

After sorrow comes joy. Suddenly, as the third of 10 sentences of the poem says. But not right away. At the end.

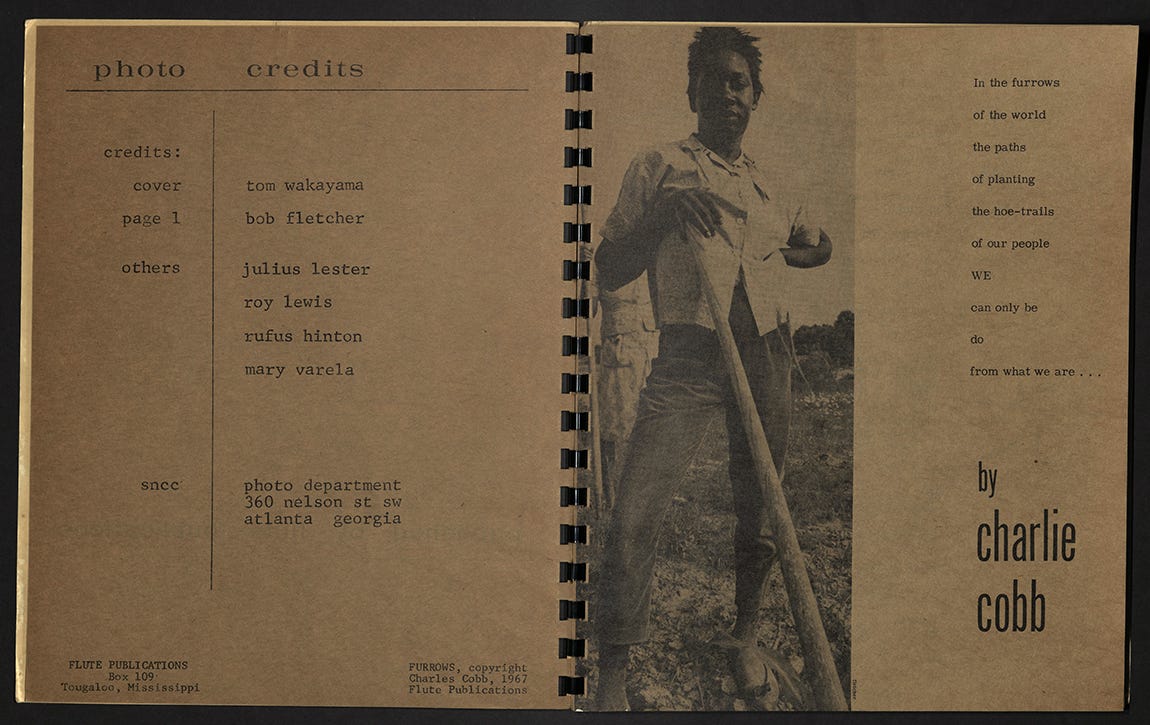

You may read Charlie Cobb’s book of poems In the furrows of the world (Flute Publications, 1967) published by Maria Valera, printed by Henry J. Kirksey, with a cover photograph by Tamio Wakayama, illustrated with more by Julius Lester, in facsimile at the website of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, from where I took the second and third images above.

The first photo above, of the back and front cover at once, comes from Book of the Week, by lyuba, on February 7, 2022 at the J. Willard Marriott Library Blog at the University of Utah.

Charlie Cobb discussed the publication of In the furrows of the world with Joshua Clark Davis in an interview on February 27, 2017. In that conversation the author called it Furrows. I have read the SNCC website refer once to the book as Hoe Trails.

Julius Lester spoke of his travels with Charlie in The Loyal Opposition: Americans in North Vietnam, 1965-1972, by James W. Clinton (Colorado, 1995), not before 1989. Charlie tells of his great-grandfather in a National Geographic article the search engine has found for me once only.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

another beautiful review with incredible context. thanks so much

Pure Gold. Please 🙏 keep these nuggets of wisdom coming.