Tonight in Washington . . . Ho Chi Minh (i) Campfires of the Resistance (i)

From poet Will Inman and editor Todd Gitlin

After sorrow comes joy. Suddenly, as the third of 10 sentences of the poem says. But not right away. At the end.

Good Days Coming

This poem is a consolation. That’s a literary mode, as learned men often have composed while in prison. You comfort yourself with a structure of thought, as Boethius and philosophy consoled one another.

The wheel of the law turns without pause.

Writing in but not of sorrow, stoic. Suspended between sorrow and joy. Not yet a happy poem, not something you would pronounce at a marriage, an epithalamion, the triumph of hope. Boethius’ own consolation ended in torment.

After the rain, good weather.

This poet speaks as from prison while imagining himself in the fifth sentence well out and up where he may view to an impossibly distant horizon an expanse of impossible green across our in fact mostly blue globe. The author did really do time, about as long as Boethius, less than many militants of the United States of America,

In the wink of an eye the universe throws off its muddy clothes.

not at all by the standards of his comrades later in the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party, who won freedom and independence then made all of their nation under their government into a prison, especially for poets,

For ten thousand miles the landscape spreads out like a beautiful brocade.

as Joseph Stalin had done to fight a war. Hey, the VC won. But their struggle required more and more happy talk. After 20 years a collection of poems attributed to the prisoner turned warden appeared in the propaganda fidei with a tale of provenance

Light breezes.

that was dodgy when I last looked into it 30 years ago. Many provenances are dodgy even outside the grasp of Stalinists. Those who hate the named author argued further that the militant Ho Chi Minh could not have written those poems.

Smiling flowers.

Hey, people also argue that Ho was not Ho, whatever that could possibly mean. People are bent out of shape. Many men could have composed those poems and any literate one could have written them. Anyone can get lucky and catch a good line.

High in the trees, amongst the sparkling leaves, all the birds sing at once.

I love the one human Taoist verse in this bureaucratic Confucian memo. After sorrow comes joy. It enjoyed wide appeal at the time among the world’s appalled bystanders to the war of the USA on the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam in Cambodia, Laos, and the Republic of Viet Nam.

Men and animals rise up reborn.

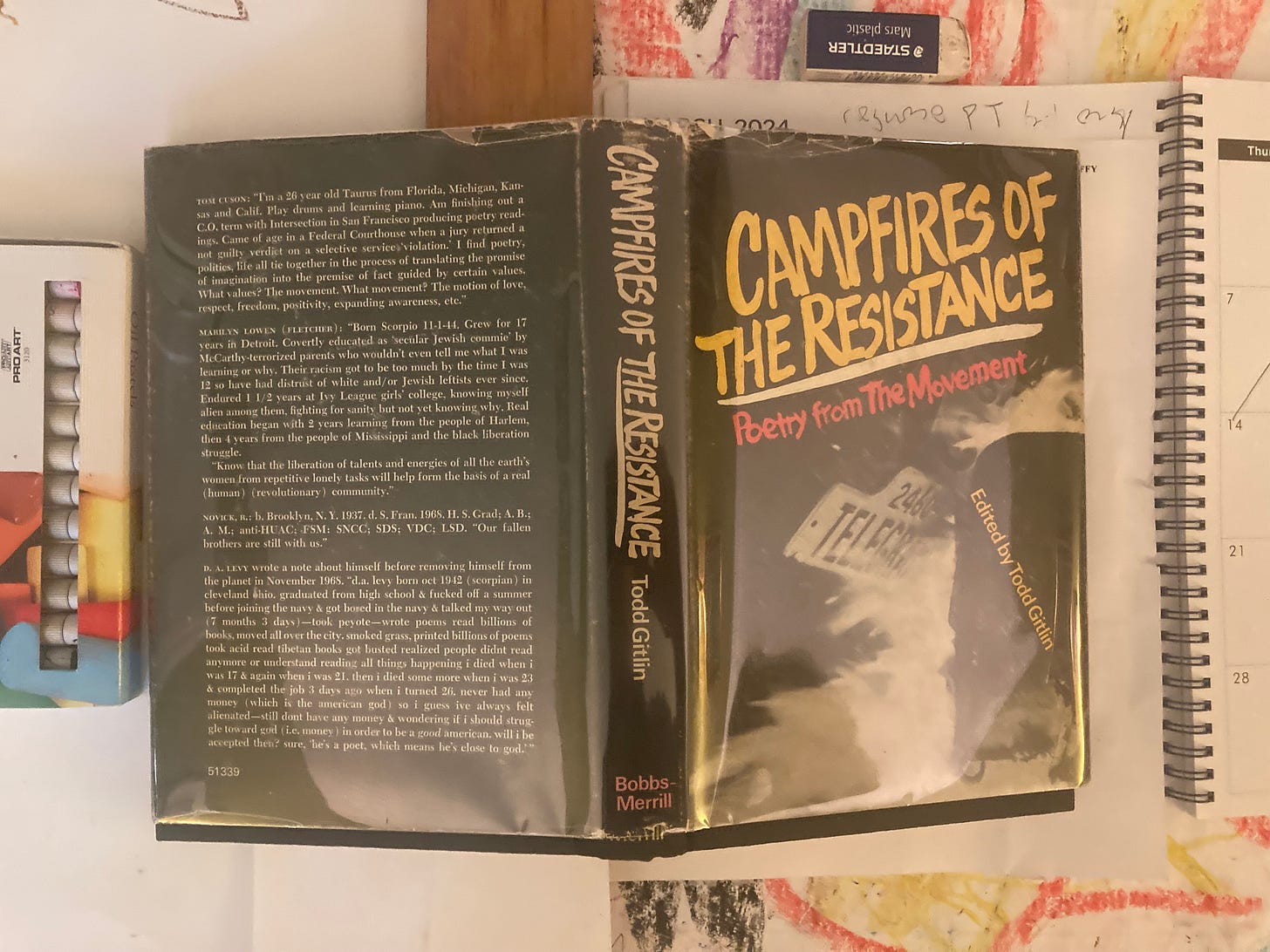

What could be more natural? Todd Gitlin gives the poem in full as the epigraph to his preface to his anthology Campfires of the Resistance of poems from his movement over the 10 years that began in 1960 with the last 5 years of our 1 hundred years’ struggle to expand the vote

What could be more natural?

and ended in 5 years’ deadlock through 1969 among voters here whether to continue or stop killing the voters of our ally to no purpose. When Todd’s collection appeared in 1971, after sorrow comes joy was still a consolation.

After sorrow comes joy.

We know for sure the first president of the DRVN wrote better than that consistently for years above his dozens of by-lines for immediate publication. Just as good as me, that is, better than those who write faster and faster than those who write better.

Ho Chi Minh. Written in prison.

Except for what could be more natural after sorrow comes joy the poem sounds like something the dim Le Duan or the grim Le Duc Tho dictated after Ho died. Maybe the cool Pham Van Dong contributed those only good lines.

That poem appeared in Viet Nam when the Party needed to improve morale while the beatings continued. ‘Look, look, Uncle was in prison too but he kept it together. Hang on.’ And they did.

Todd in that spirit began his preface with that whole poem not just the good bit as an epigraph usually does. Ho had won a hearing here first for his defiance and then endurance and after death this offer of hope.

I looked for Uncle in the rest of the book. We didn’t call Ho that here then. Our uncle was Sam. Uncle’s letter sent Christopher Hillman and Gram Parsons heading for the nearest foreign border (Flying Burrito Brothers, 1969.) Their song “My Uncle” is a more lived and lively poem than Uncle ever wrote.

FEVER AND HEALTH

I found Ho here and there throughout the book mentioned as an emblem of resistance, or in a slogan quoted by more gifted poets who also had spent an entire adult lifetime to that date, 5 or 10 or many more years, in struggle and often in prison. All the while they had argued with each other.

Fever is beautiful the twinkling

Ho never did that. He did not do time in the French prisons where his comrades elaborated their thought. Ho had nothing complicated to say. When I first arrived in Ha Noi and heard of the Center for Ho Chi Minh Thought, I thought it was meant as a joke.

campfires of the resistance

By contrast, a center for the study of Joseph Stalin’s thought would make sense. H. Bruce Franklin, union mariner, university researcher, a founder of scholarship on Herman Melville, published an entirely serious collection of Uncle Joe’s theoretical work 1 year after Todd’s collection of poetry from the movement appeared.

the scorched earth and the strait pass,

Bruce was in his day the youngest man to win tenure at Stanford. They fired him for joining the movement not for editing Joe. You can think with Stalin, though no one does in this anthology because of course we had our own dialectics. You can’t think with Ho.

though it is terrible to watch

Uncle was a sloganeer for his Party. He had taught practical skills at Moscow and given introductory lectures at Whampoa. The advice of the Communist whose nation still stands as Joe’s does not was to keep it simple. Bits of his happy talk stand out in this collection of passionate reflection after many American arguments.

the history of the disease

There is nothing more precious than freedom and independence. The frequent citation and quotation of Ho’s cheerleading in our movement gave many the opportunity to say that ours also was for dummies. People who say that spent the 1960s making a career in a university profession and no democratic politics at all.

and the wrong banner flying. . . . [period and ellipsis sic]

Dependent bourgeois, institutionalized, subordinated, in sports jackets or black outfits they are naive and unsophisticated. They have never argued Stalin with a Stalinist. Todd by contrast was one of the militants of the quarrelsome movement who also won a terminal degree and a university career. There were very few of them as there are only so many hours in the day.

Paul Goodman

Todd did great and retired from Communications at the first and formerly public university, Columbia, in our major media center, New York. Bright and hard-working, a personable lunk, Todd had been in his youth the Al Gore of the Students for a Democratic Society.

Tonight in Washington . . . Ho Chi Minh

It was not the professor’s fault that after 1980 he became the engaged intellectual of his 1960s whom the New York Times could find for a Democratic quote. An authority. Blamed Ralph Nader for talking back to both parties. But in 1971 young Todd spoke fresh from 10 years of discussion and action in a continental movement of politics such as the VC had rooted out from their own revolution.

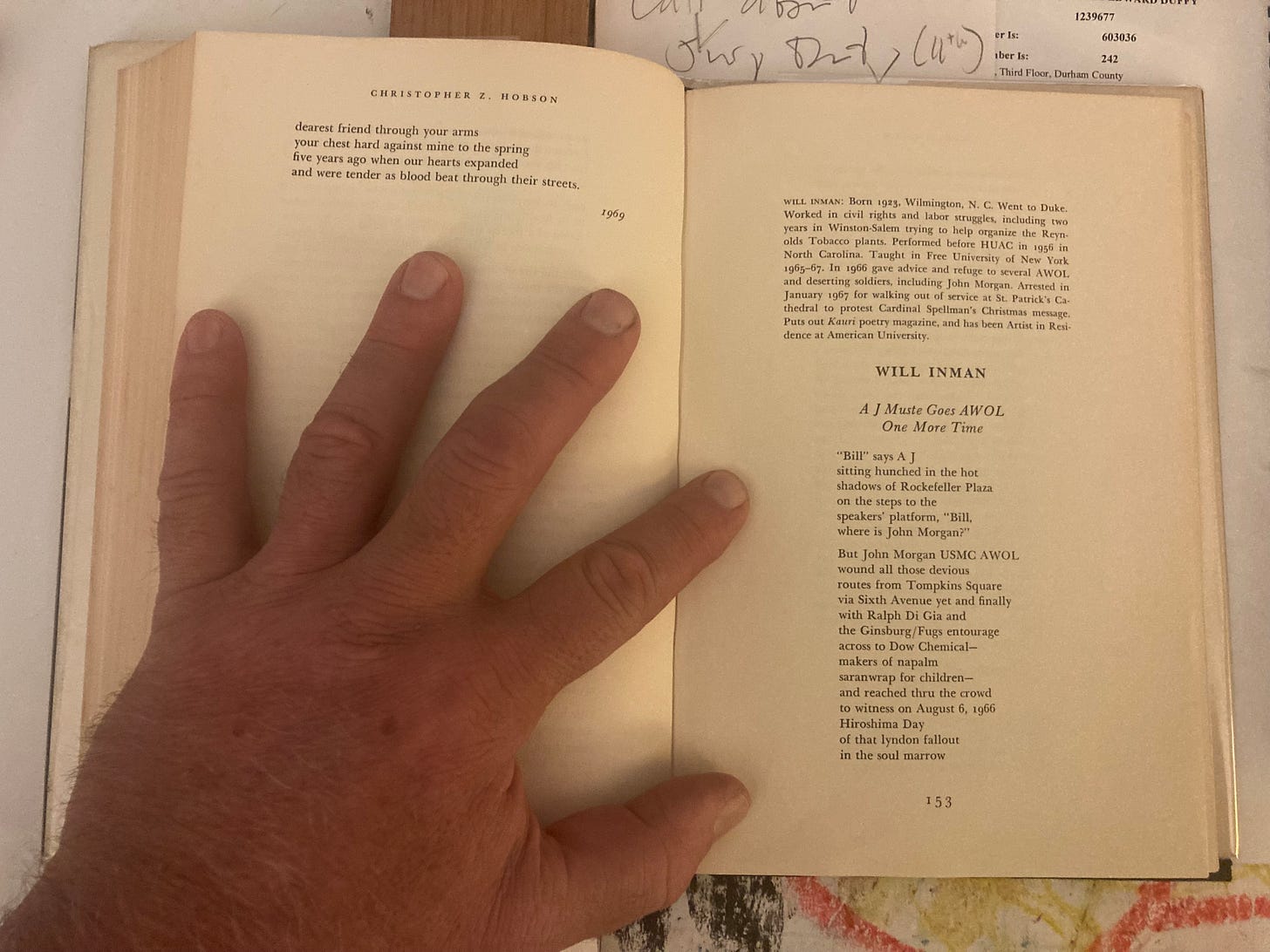

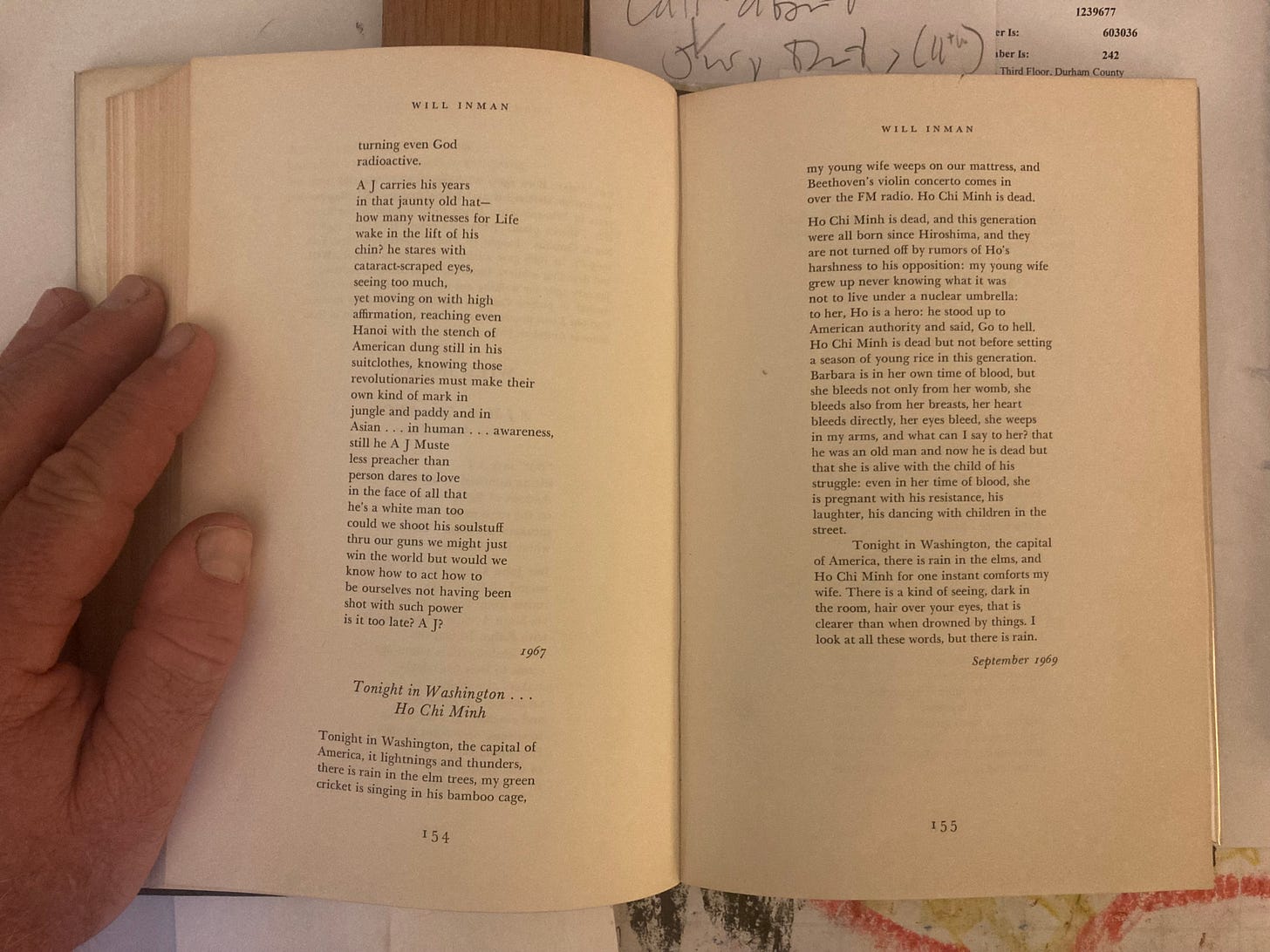

Tonight in Washington, the capital of America, it lightnings and thunders, there is rain in the elm trees, my green cricket is singing in his bamboo cage, my young wife weeps on our mattress, and Beethoven’s violin concerto comes in over the FM radio.

Sure, Todd gave in full those wooden sentiments from Ho as an epigraph for his preface. But he put on the frontispiece, the page facing the title page of the book, verse from Paul Goodman in whose Walt Whitman lines fever is beautiful the twinkling campfires of the resistance live the anarchist, homosexualist, libertarian, pacifist, psycho-analytic discussions of the engaged 20C beyond the grasp of victorious Communist parties.

Ho Chi Minh is dead.

Communists fight for a nation in a front alongside the other debating societies then after victory use socialist thought as a facade, that other kind of front, for authoritarian rule. After 1976 dead Ho met many new readers from his old front in prison where they had to praise him in cheerful song. After sorrow comes joy. Boy do the survivors hate that poet.

Ho Chi Minh is dead, and this generation were all born since Hiroshima, and they are not turned off by rumors of Ho’s harshness to his opposition:

I like Communists. I used to go to the funerals of the old guys around here to sing the International, and Solidarity Forever to the tune of the Battle Hymn of the Republic. I adore a Communist who is not in power and is not working for some other nation. Before Todd’s revolution began in 1960 the Communist Party of the United States of America made what revolution they could here in North Carolina.

my young wife grew up never knowing what it was not to live under a nuclear umbrella:

They organized workers across the 1940s and 50s when the big-labor victors of the struggles of the 1930s didn’t bother. They stood in person against lynching and for the vote when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People didn’t dare. Brave and full of hope beyond words.

to her, Ho is a hero:

Uncle Ho, the human being who led a nation to expel the foreign invader and unify the country, appears in Todd’s anthology once only, in a poem from a Communist of North Carolina, 20 years younger than Ho, 10 years younger than Paul, 20 years older than Todd, 35 years older than me. Will Inman fashioned his nom de guerre by adopting his mother’s maiden name to suggest Will In Man.

he stood up to American authority and said, Go to hell.

She had given birth to William Archibald McGirt, Junior at Wilmington 25 years after the insurgency burned out the Republicans black and white there in 1898. When we drove Will Inman from our one-party state he became a librarian in New York and a publisher to the new movement.

Ho Chi Minh is dead but not before setting a season of young rice in this generation.

His poem is breaking news, laid out as a newspaper column, spoken as a radio program with Beethoven in the background. Tonight in Washington, the capital of America. That news came on September 4 or after. The VC had delayed announcing Uncle’s untimely death on the same date when in 1945 he had declared the independence of Viet Nam.

Barbara is in her own time of blood, but she bleeds not only from her womb, she bleeds also from her breast, her heart bleeds directly, her eyes bleed, she weeps in my arms, and what can I say to her?

They were that scared. Will is about as old in 1969 as Ho was in prison. He’s got a wife half his age, also a dissident, who has not yet been around the block. She is stricken. She doesn’t care that Ho became a jailer to his people. She has never lived under a 1-party state as Will has.

that he was an old man and now he is dead but that she is alive with the child of his struggle:

To her, Ho is a hero: he stood up to American authority and said, Go to hell. Yup, that’s it. That is what the world outside Viet Nam me inclusive loves him for. That is what he is doing in all those cameos in Todd’s collection.

even in her time of blood, she is pregnant with his resistance, his laughter, his dancing with children in the street.

Will doesn’t try to tell his wife anything. Barbara is in her own time of blood, but she bleeds not only from her womb, she bleeds also from her breast, her heart bleeds directly, her eyes bleed, she weeps in my arms, and what can I say to her?

Tonight in Washington, the capital of America, there is rain in the elms, and Ho Chi Minh for one instant comforts my wife.

Woman’s got her period. She just learned of her hero’s death on the radio. She grieves. Would you try to tell her anything? How young are you?

There is a kind of seeing, dark in the room, hair over your eyes, that is clearer than when drowned by things.

Time to write a poem. Barbara may read it later. She may find consolation in its flight of fancy, that Ho has seeded her with joy: his laughter, his dancing with children in the street. Maybe not. She is the one with the womb. Will is the one born where slaves grew rice.

I look at all these words, but there is rain.

It’s a poem. You read it. On the 2 pages of the book the layout is as from a news service. Compare the right-hand edge, flush right but not justified, to the wildly jagged one of the poem before, on hearing the death of his own hero A.J. Muste.

September 1969

Until just now I had thought that A.J. was an Aloysius Joseph, a Roman Catholic. Turns out he was Abraham Johannes, a Dutch-speaking immigrant just like my grandfather the same age also from the same Reform church in the same place in Michigan and the same Calvinist college. Both pacifists though mine served in the American Expeditionary Forces then as chaplain to the American Legion.

A.J. was like Paul Goodman everything Ho Chi Minh, Le Duan, Le Duc Tho, and Pham Van Dong wiped out in their Viet Nam. Civil rights man, pacifist, socialist, union man. Ho and A.J. got along great, of course, the one time they met. You do that in friendship politics. I have done that.

But A.J. and Will really were comrades and friends. That is one broken-up poem, jagged lines in the heart. Tonight in Washington . . . Ho Chi Minh is instead a consolation, balanced. Look within the newspaper column at the sonnet-like form. Will did a degree in English at Duke in early New Criticism days while working in a defense plant.

7 lines of introduction, body of poem 3 times longer at 21, then 7 final lines nearly repeating the first 7 in conclusion. A well-wrought urn, as Cleanth Brooks taught at that time. Stanzas turned as on a lathe.

The good bit, rising above Will’s verse as after sorrow comes joy does from Ho’s sentiments, is the first sentence of the 3 of the last stanza. Tonight in Washington, the capital of America, there is rain in the elms, and Ho Chi Minh for one instant comforts my wife.

Consolation. Between sorrow and joy. What could be more natural?

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.