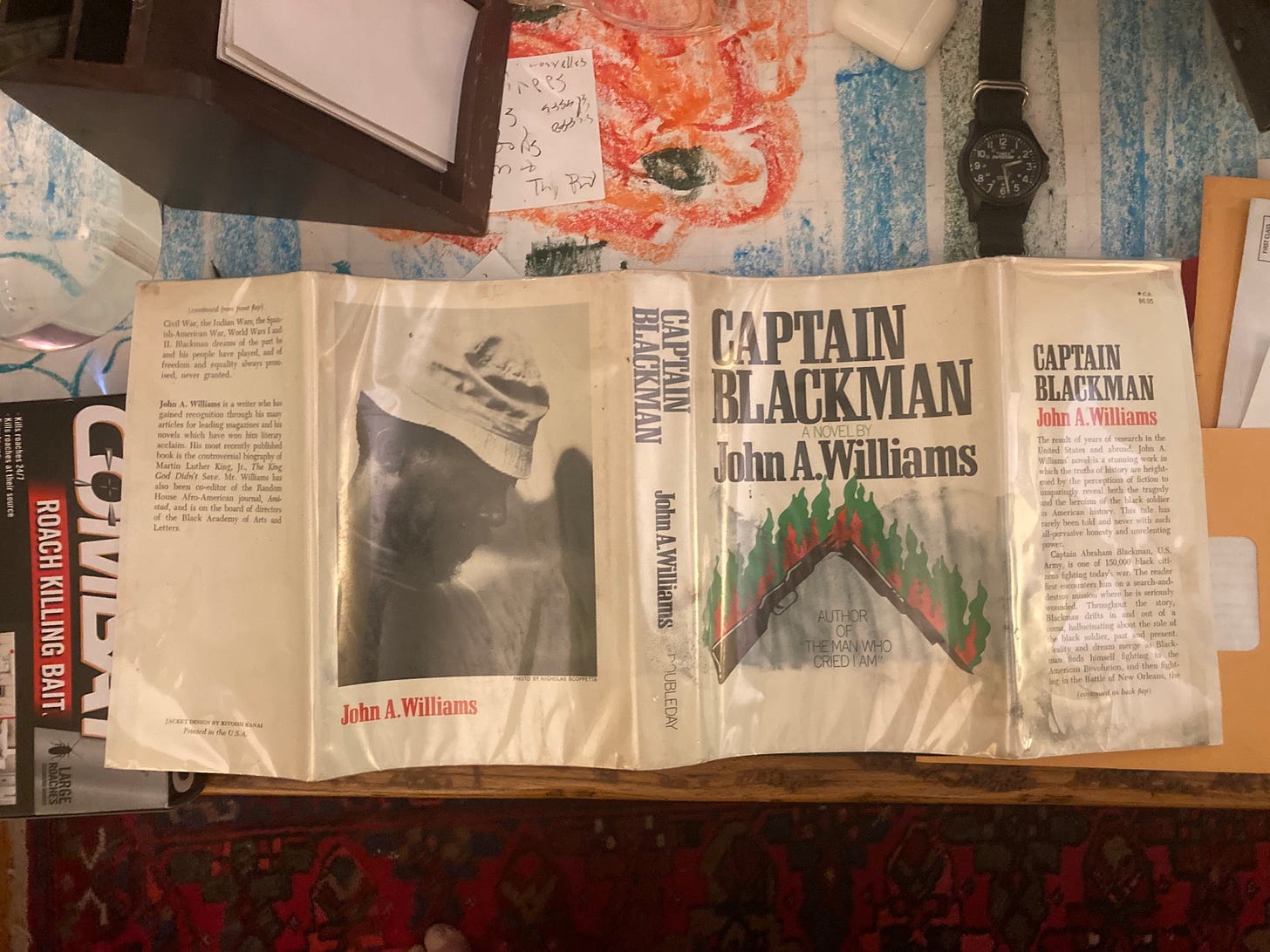

Captain Blackman (v)

from novelist John A. Williams and the war for the United States of America

Johnny Griot finishes firing one clip from his M-60, then signals Antoine forward before slipping in another clip to cover him. What could that possibly mean?

The M-60 fires a disintegrating link of 100 or 150 rounds. The Browning Automatic Rifle fires from a magazine of 20 rounds, meant for what Johnny is doing, killing some other guy through the bushes with the heavy rounds we use for deer,

in this case an enemy with an AK-47 firing lighter bullets usually from a 30-round magazine. Anyone firing clips that day would have been locals with antiques, outgunned rather than using the heavy weapon in a squad.

Well, we could say, John A. Williams served as a sailor, not a soldier. But our Navy used the BAR in his day, and the M60 afterwards, neither with a clip. Indignor quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus, Horace remarks in his Ars Poetica.

It ain’t right but even Homer nods. The author John should not be telling us about clips, and his Johnny Griot, which means historian and poet together, should not be firing them. Captain Blackman is otherwise all about how things really have been.

Facts we can check become important because Chapter 4 proceeds from the firefight as the first chapter did to a conversation that must have taken place among peers of the realm on how to preserve an unjust social order. We can’t check those intimacies. We infer from the facts.

Blackman’s ghost eavesdrops at a banquet in Cincinnati, named for the original officers of the United States, where some Cabot, not any specified member of the Boston clan, fails to convince the hereditary tycoon Cockrill to at last give up slavery, for the common good of rich men. Mark instead lent the Confederacy their gold. And so war came.

Sergeant Blackman soldiers through Port Hudson, where generals Banks and Ullman squandered lives of the freedmen, witnesses the energetic disintegration of the creole Captain Cailloux, then the massacre of the emancipated at Milliken’s Bend, charges over the body of his abolitionist Colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, who the sergeant later leaves in his pit with his men when Blackman leads a burial party,

then, after another massacre at Poison Springs, gives over all humanity as the enslaved who rallied to the Union and the white soldiers whose deaths were no longer necessary but imperative kill each other hand to hand until their arms grow weary. Civil war.

No quarter to the Rebels,

No quarter when they call,

No quarter to the Rebels,

Damn them, kill them all!

This was the fifth Viet Nam letter of 5 so far presenting Captain Blackman by John A. Williams. The first posted on April 4, 2022, the second on May 4, 2022, the third on June 6, 2022, and the fourth on July 23, 2022.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

Thanks, very good.

thank you for your careful reading and writing and sharing...just amazing!