We left Captain Abraham Blackman, United States Army, supine on the forest floor his head resting against a stump. It is the position in which I continued, from my couch,

to read the story we share in mind as he bleeds and I read. Abraham had leapt to his feet firing toward many concealed attackers to prevent his own men from walking into the killing zone.

"In a dream he saw them, these men in their wigs. They were in an inn in Delaware, a colony halfway between their homes in Massachusetts, Virginia, North and South Carolina. Many had not met except through letters brought by the packet or post, but they were firmly bound together, sharing in the profit and loss of each venture, all tied to the sea and the land, all based on people who were black."

Our captain eavesdrops on a conspiracy, like the ambush he had walked into. He attends to the whole meeting as the revolutionaries speak in plain terms of their strategy to take the whole continent and the Pacific beyond.

"Knew it all the time," Abraham exclaims to himself. That is to say, he merely suspected previously but now has found proof as he bleeds out in delirium in the Republic of Viet Nam.

The history that the captain has taught the men he just saved is an accretion of facts as the cliffs at Dover are the skeletons of sea creatures as they lay down dead over generations. It is the history of black men and women building and defending the United States.

The historians that Blackman has prepared his lectures from are all the more reliable because most did it as a hobby for plain people to read. Without the shelter of university jobs their books have survived challenge and neglect by the rude and hostile.

Every assertion you will hear from me as the captain relives his black history as a soldier of our Army from Lexington on is the mere truth. "This must be distinctly understood," as Dickens wrote of dead Marley, "or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate."

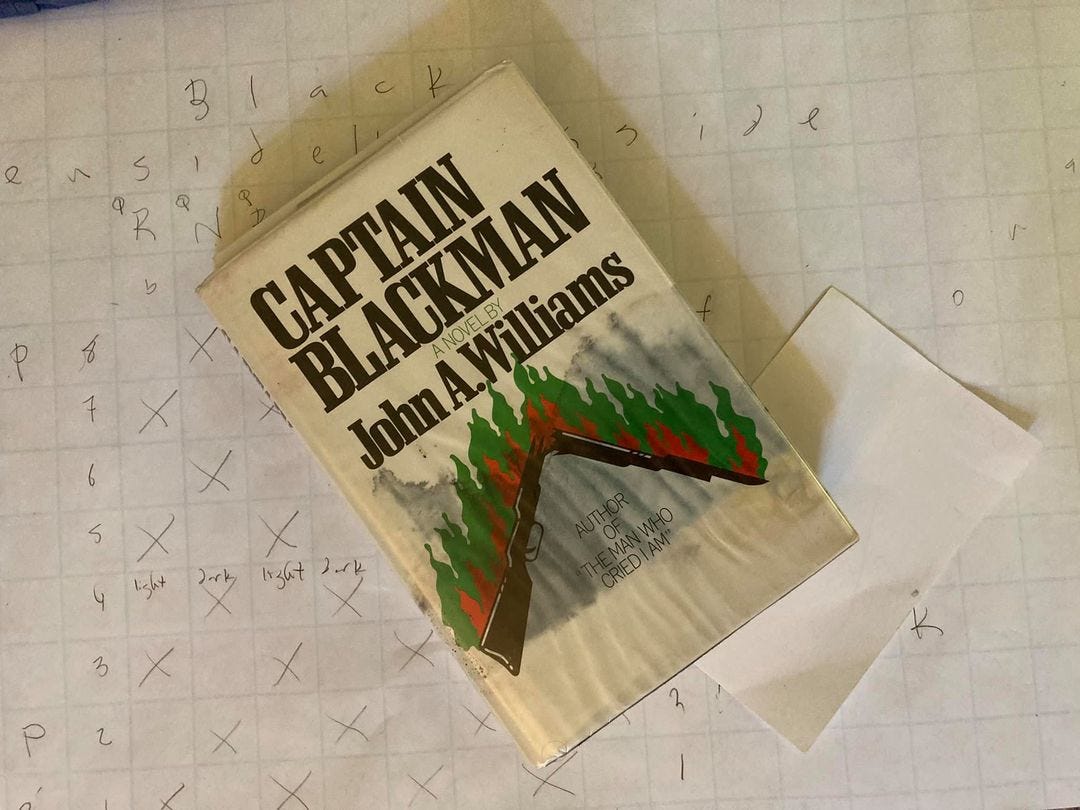

So why does the novelist John A. Williams begin the journey of Captain Abraham Blackman through the history of the United States Army, which would would not have come into being without black Americans,

without which there would be no black citizens of the United States, why does he begin this history built of stubby facts, with instead a conspiracy theory? Well, John reads and retails history.

But as a novelist he is indeed a conspiracy theorist. His best-seller, The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), proposed that the Central Intelligence Agency worked to eliminate the diasporic Africans from the human race.

It has become one of those novels taken as authority by those bent severely out of shape. I think they are mistaken because for instance two officers I know of busied themselves in their cover jobs in the first days of the United Nations finding apartments, doctors and schools for African diplomats in white Manhattan.

We also know of an actual Central Intelligence Agency conspirator, a colleague and contemporary of John in literature, the novelist and officer E. Howard Hunt. We have got racks of his conspiracies, fiction and non-fiction alike, and none of them have to do with black Americans.

More fundamentally, in Abraham's dream, the revolutionaries conspire to use the forced labor of black men and women to corner the common man to take up the rich man's cause of liberty. That is plausible.

Something like that could have happened and no one would have taken notes. The conviction that such a conversation as Abraham overhears at the beginning of his rehearsal of the history of the United States

did take place mounts as the facts grow like Dover's cliffs when you approach them from the sea. How did you not know any of this? How did those involved not know?

What on earth is Captain Abraham Blackman doing on the forest floor as his young men approach to kill the Vietnamese? We start again next time at Lexington.

This was second Viet Nam letter of 5 so far presenting Captain Blackman by John A. Williams. The first posted on April 4, 2022, the third on June 6, 2022, the fourth on July 23, 2022, and the fifth on February 16, 2023.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

Promotional copy:

Black Americans are the original and unique citizens of the United States. Atomized individuals from the longest-settled and most various human population,

they have brought forth here among the white settlers from across the Atlantic and the Pacific and the original settlers from over the pole

a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Eyes on the prize, the invasion of the Republic of Viet Nam

was the first war through which they all could rise so far as any man may go. Many did. But it is rough history to tell, so I have found myself

telling bright, learned teachers every school year for 30 years about this prominently published, straightforward novel set among black Americans in black history in Viet Nam.

Here I go again, the second of 3 Viet Nam letters I have written so far out of maybe a dozen total to come, about Captain Blackman who rehearses all of American history as he bleeds out in Viet Nam.

The novelist John Williams is dead now himself. Please join the congregation for his remembrance and those of my other saints by subscribing for free.

$50/year will patronize all the other readers. $250/year will build the enterprise. We are a charity, like church or the theater. You may deduct any support from income before tax.