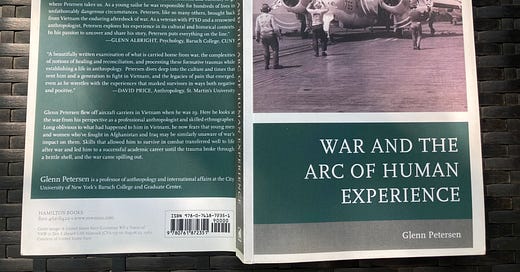

Glenn Petersen worked on a radar plane off an aircraft carrier as shown when I was about 5.

15 years later I used to ride a cargo net from the deck of a tender to above a freighter then down through hatch after hatch to the hull and back up and over again at sea further north in the Pacific while the cautious walked up and down a plank over bumpers the size of Volkswagens as the ocean lifted us all up and knocked us together hard again and again.

I refused to work directly under a cargo net, though. I wasn’t crazy. I wasn’t under orders in the Navy.

This other seaman turned anthropologist writes of work at sea:

It’s not that people are trying to kill you, but everything that happens there combines to create conditions likely to kill you.

Glenn speaks here specifically of work on the flight deck of a carrier before he even gets in the plane and takes off. Reading about that chaos in the dark, cables snapping and propellers whirring by a sheer drop into the ocean, was difficult for me emotionally but made me feel more warmly towards my own young and stupid work under a cargo net 5 decks down.

And the crews must get their work done amid this array of things trying to kill them. I think of all this routine chaos as “everyday danger,” and it’s a notion I’ll be grappling with at length in the following chapters.

“Everyday” is a term of art among ethnographers, in that sense not an everyday word although many of us use it every day. We say “everyday life” to mean both the vast uncharted spaces of personal experience and the tiny scope of individual existence. Everyday you enter an elevator, go up and come back down: where do you go?

What does it all mean?

I’ve been trying to explain why training for combat entailed much more than just skill and knowledge. It was also meant to instill in me ways of seeing and understanding things, and ways of thinking about myself and my duties. Much of this had to do with my job running the radar and controlling interceptors, and much of it had to do with working on the flight deck and keeping the aircraft operational, but the training that had the deepest impact on me was my experience with the Navy’s SERE school, that is, its Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape program.

There is everyday life, and then there is the initiation that explains your life to you when you recall the one after living the other.

SERE training intensified all the experiences that shaped the contours of my psyche before I went to war. It taught me why it was my patriotic duty to resist torture, that is, to allow myself to be tortured.

And why was that?

And then we were in the thick of it, a part of what Navy hands called the Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club, out on Yankee Station. I’d like to begin with a thoughtful account of what we were supposed to be doing in Vietnam, but it wasn’t entirely clear to us, even at the time.

Such was simply the case. Earnest young men Glenn’s age called up the State department from 1965 on to ask in sincere inquiry what they would be fighting for and there wasn’t even a lie. Nobody had any idea.

There sure was a lot of equipment, though. Glenn tells the story throughout this book of his progress into the war machine. His everyday danger was everyday war maintaining and operating heavy, high-voltage, high-speed lethal devices.

Landing on a carrier - technically an “arrested recovery” or simply a “recovery,” but much better-known in the business as a “trap” - is a lot like the launch, only hairier. Much hairier.

Glenn discusses his landings at length. They were much crazier than swinging on a rope between two ships banging against each other in the middle of salty nowhere.

Pausing to focus on the daily return to base, while emphasizing that it was the most dangerous moment of each sortie, is a striking way to tell a war story. There is nothing far-fetched about it.

The author conveys just the opposite, the black and white high relief of a sober consideration of life and death. That is the gritty half of the metaphor, whose more airy meaning stands there in the subtitle, Arrested Recovery.

More when our hero returns, and returns, and returns next month and many more after that.

Viet Nam letters has addressed War and the Arc of Human Experience by Glenn Petersen 7 times so far. We began on February 19, 2022.

The second posted on March 7, 2022, third on March 28, 2022, fourth on April 27, 2022, fifth on May 30, 2022. Then the seventh on June 20, 2023.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.