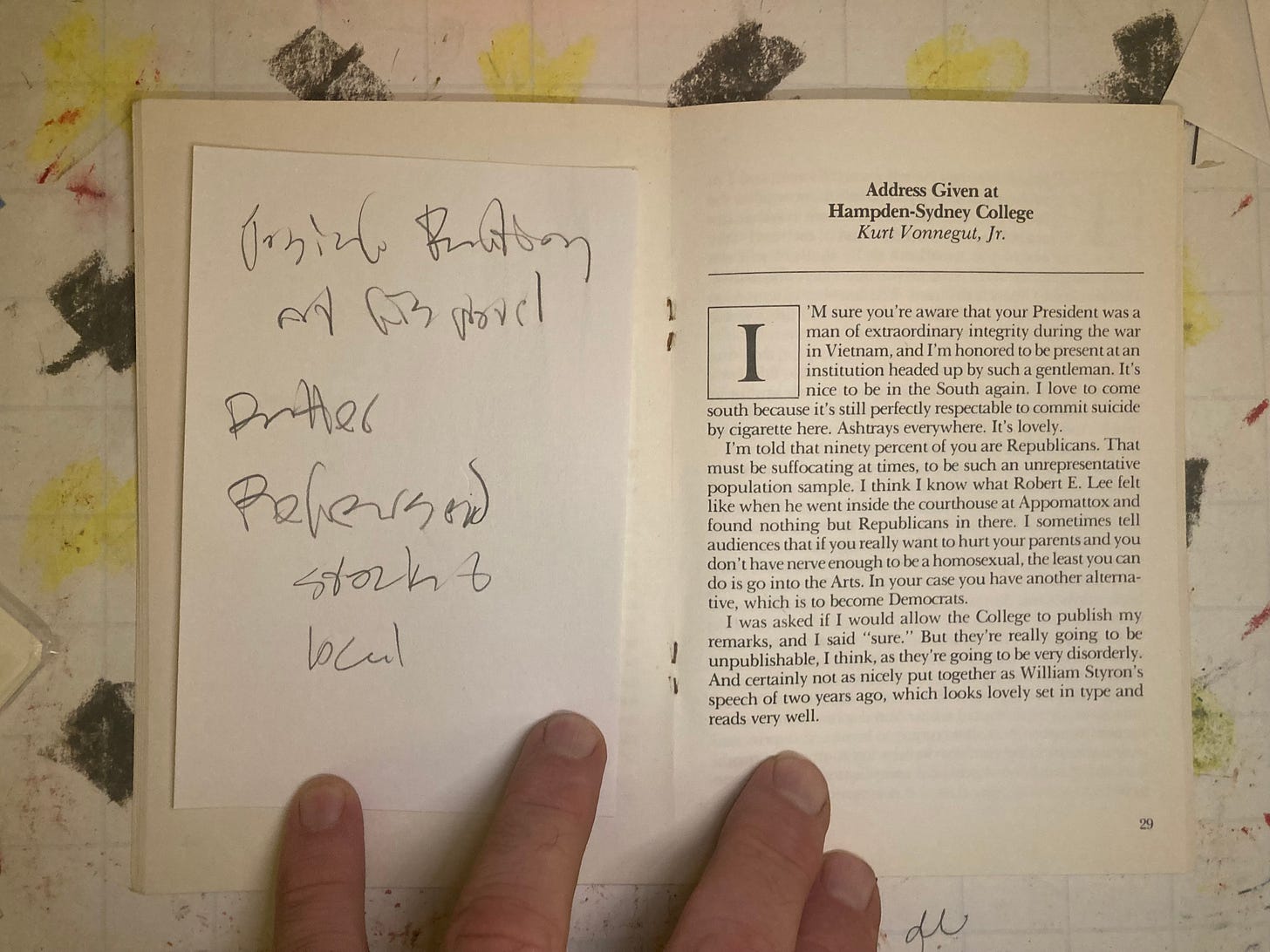

Vonnegut at Hampden-Sydney (ii)

from critic Alan Farrell, novelist Kurt Vonnegut, and editor Michael Boudreau

Good people,

He recognizes the audience in goodwill without distinction of rank, role, or sex.

our text for this evening

Sunday, September 25, 1983. Not the tenth of the month when the Church of England reads that psalm.

The college is Presbyterian and the critic is a Roman Catholic whom I have observed carrying out a solid handful of the 7 corporal and 7 spiritual works of mercy across 4 decades. Both churches recommend Psalm 53 as liturgy but neither specifies an occasion.

is taken from

Ah. Is taken. No church suggests any excerpt. You read the whole thing. This is not vespers. The critic chose the text and the verses.

the words of the Psalmist.

That would be David. King of the Jews, if you please, in Farmville, Virginia and everywhere else.

The fool hath said in his heart, “There is no God.”

Rashi, writing 1 thousand years ago in France - remember that, in France - considered that David sang 3 thousand years ago of Rome’s destruction of our second temple at Jerusalem 2 thousand years before present.

Jews have read Rashi on this psalm in notes like this one whenever in our subsequent dispersal we have studied the song itself. Did you think Billy Pilgrim was the first to become unstuck in time?

And also from the words of Kurt Vonnegut:

Antiphony. We are reading psalms here.

I wish I could bring light to your tunnels today.

Hang on it’s a lamentation as from Jeremiah who hailed Babylon’s destruction of our first temple at Jerusalem 2 thousand 5 hundred years ago. After him in the Roman alphabet comes Kurt who returned from the firestorm of Dresden 75 years ago to say that things are getting worse.

Kurt is speaking to new graduates at Bennington College in 1970, with reference to our government’s defense in 1967 of the strategy of the United States Army to support Saigon against Ha Noi in their war for Viet Nam, fighting the People’s Army in battle while rolling up dissent in the countryside.

That tunnel was dark so we disengaged and by 1970 most even of that minority of young Americans who had taken part one side or another in the fate of Viet Nam had moved on to their own tunnels. The novelist arrived at their commencement with even more bad news.

I’m sure you’re aware that your President was a man of extraordinary integrity during the war in Viet Nam

No he is certain that they aren’t. In his 1970 address at Bennington the novelist had similarly introduced his views on the first scene of the second act of The History of Henry the Sixth, part 3, by William Shakespeare.

“You will remember,” he said, as they didn’t. The president at Hampden-Sydney 15 years later was Josiah Bunting. Look him up. A tall marble-mouthed stuffed shirt with good hair who spent 20 years saying fine things about the humanities in higher education as they retreated but well yeah of integrity.

As a junior officer he had dissented in public to his ilk’s conduct of his war, uncommon, then wrote one very good novel about officers, rara avis. After the war he hired the critic not once but twice, unique.

Kurt doesn’t say anything specific about Josiah’s integrity and nothing about his novel. The lifelong witness and professional novelist had picked up some chatter about the amateur and made a gracious opening remark, respectful of sleeping dogs.

It’s nice to be in the South again.

And so on.

I am told that 90 per cent of you are Republicans.

The visiting lecturer breaks the ice with jokes fashioned for the occasion. We catch the novelist here as he begins his career as a humorist in the manner of Mark Twain, working as seriously as a showman as he did on his books.

I was asked if I would allow the College to publish my remarks, and I said, “sure.” But they’re really going to be unpublishable, I think, as they are going to be very disorderly.

Mistaken, in the event, as the College did publish those remarks. Furthermore, arch and disingenuous. Rhetoric, the real thing.

And certainly not as nicely put together as William Styron’s speech of two years ago, which looks lovely set in type and reads very well.

Plain mean. Ambitious, competitive, envious chain-smoking spin-rack novelist taking aim at the drunken Southern WASP with fancy publishers.

The 1970 address at Bennington the critic had excerpted the week before came from a 1972 collection of stray pieces, left-hand work from the newly-famed novelist’s early days in book-length fiction. 1983 at Hampden-Sydney was in the beginnings of a new enterprise, after Kurt had said goodbye in Breakfast of Champions to the cast and concerns of his first round of novels ending with the slaughterhouse.

It was also a time of something new for the critic Alan F. Farrell, professor of French. The Hellenist, Latinist, speaker of many Romance and more than one German language career commando started giving addresses, too. He was pushing 40, same age as when I later became an anthropologist. Kurt was leaving 60, same age as I am now.

They both used to be older than me. One day you too may be this old. We are walking the talks of 2 of my great contemporaries, whom I know as you never may, 1 page at a time.

This is the second Viet Nam letter of 2 so far about the works of Alan Farrell. The first appeared on August 21, 2023.

The critic already has appeared in the sixth letter of 7 so far on Dawson’s War by B.K. Marshall, June 18, 2022.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

Share