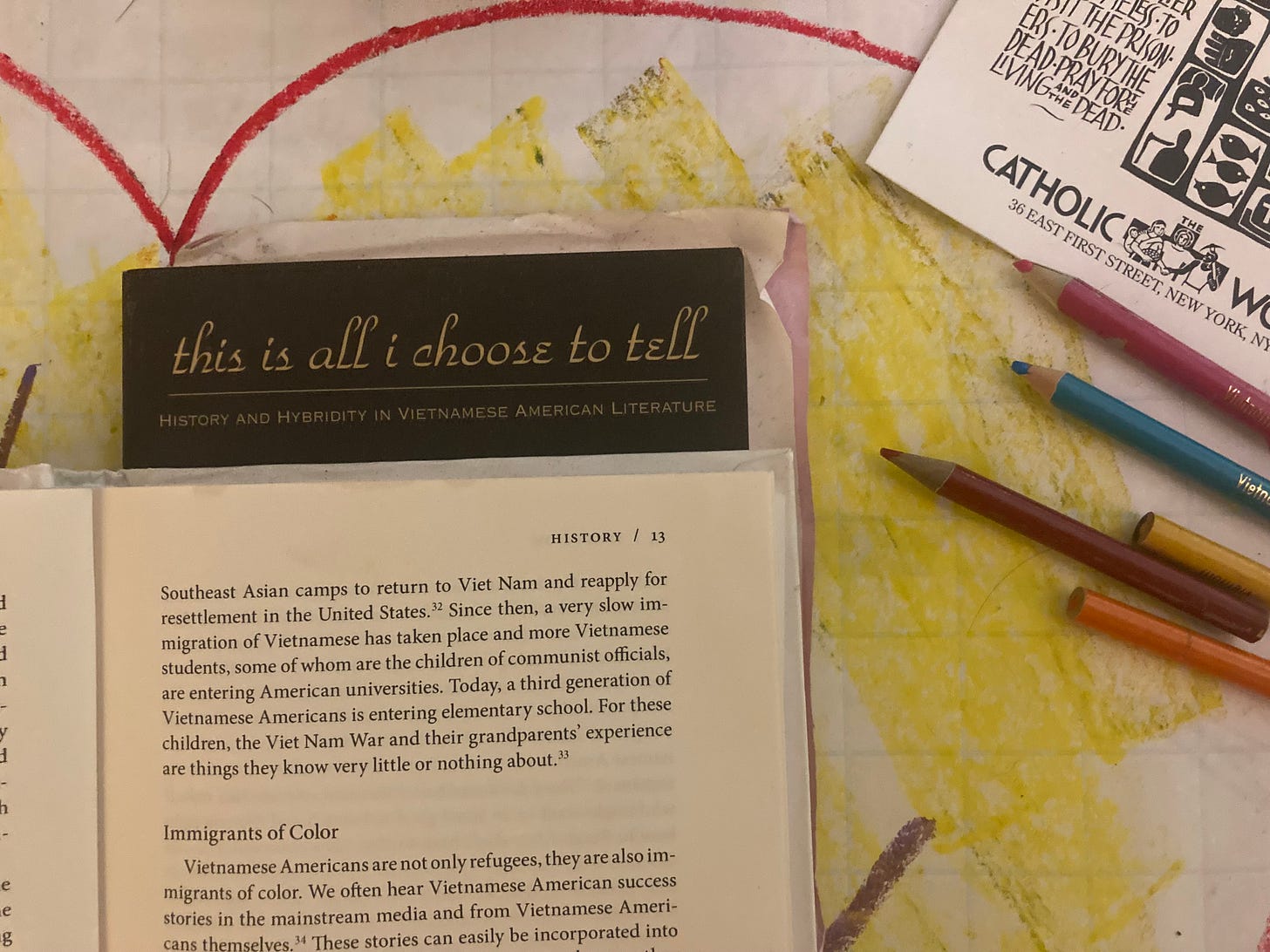

This Is All I Choose to Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature (iv)

from critic Isabelle Thuy Pelaud and ethnic studies

“Today, a third generation of Vietnamese Americans is entering elementary school. For these children, the Viet Nam War and their grandparents’ experience are things they know very little or nothing about.”

Today. The copyright year of the book, 2011? So now in 2022 that third generation is still in high school. Across that span of my own life, age 5 to 18, I knew all about the Great War when the men in my grandmother’s village died then she married my grandfather from the occupying force.

And of course when I entered kindergarten in 1965 we occupied the Republic of Viet Nam and it was all anyone talked about until 1972. Then they stopped. I became curious. In 1975, the autumn after Saigon fell, I entered high school where I began my inquiry into what that was all about.

Fantasy, I wrote in my first essay like this one, after reading all of the United States fiction and history alike, in English, I found in our Class of 1945 library in 1976. Around 1989, long out of school, making books for publishers, I joined a friend who had started publishing those American veterans who wrote against fantasy and forgetting,

and made friends with one of the original Vietnamese immigrants, who had thrown out his television when his new country invaded his old one in 1965. When Saigon fell in 1975 and people started drowning on their escapes over the 1980s he translated a body of Vietnamese poetry for their children.

In 1991 I started using Vietnamese language and entered in the community and family round of the Vietnamese year, first in my native New Haven, then at Ha Noi over 2 years, then when I moved here to North Carolina, then for a year in Paris. My sense of Vietnamese people weighs strongly towards the death anniversaries I have attended where they remember ancestors often dead in some war.

Furthermore, many of the Vietnamese Americans I keep up with here on the interweb are historians of Viet Nam. My sense is that Vietnamese young and old live in the past. In my South, of course, the defeated states of the Confederacy, we also see the life of the ancestors in the present.

History, this first chapter of the first section, Inclusion, of This Is All I Choose To Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature by Isabelle Thuy Pelaud goes against that grain of my life like fingernails on a chalkboard, if you remember what that sounds like. So I bet she’s right.

One thing I know for sure about Vietnamese Americans is they know more about America than I do. They follow Hollywood and money sports. They have their finger on the pulse. Me? My grandfather christened me in the church that founded his Massachusetts town.

I grew up in the congregation that founded my town in Connecticut, whose denomination founded my national college there, where I studied after my national high school in New Hampshire. Federalists established both schools to serve the new republic as we graduates have done ever since.

That’s how I assimilated to the common world. The Dutch-speaking branch of my family in Michigan has more than one cemetery full of my relatives. The living can tell you all about all those dead and do. It is easy to mistake me for a typical American, and that is how I see myself, but that is a mistake.

Most Americans are raised rather in television studios in Burbank where my background appears only as a backdrop without depth, for costume dramas. Isabelle is speaking to these real Americans, about the Vietnamese who have joined them.

Neither audience nor subject know beans about the United States let alone Viet Nam. Next time let’s see what the Franco-Vietnamese American literary critic and professor of ethnic studies tells them.

This was the fourth Viet Nam letter addressing Isabelle Thuy Pelaud’s This is All I Choose to Tell. The first went out April 11, 2022.

The second went out May 11, 2022 and the third on June 15, 2022. The fifth posted on October 19, 2022.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of Viet Nam letters is a thumbnail version of a photograph of me speaking on a Veterans Day with the novelist David A. Willson.

“fantasy and forgetting” - a danger (and inevitability) that human history will keep repeating itself until we retire the species. Some of your contemporaries feel your memories and stories in their bones Dan. Count me in. Viet Nam is written in my Blood if not my intellect. Hard for me to imagine anyone born in the US between 1955 and 1965 lacks this painful and exotic streak. V