Yesterday I lay down and read a dozen and more chapters as I have longed to do, to read this novel like a dream. It is a dream I have had before, told by an older friend of mine, the novelist Duong Thu Huong,

in her Paradise of the Blind, translated into French by my friend Phan Huy Duong and English by my college contemporary Nina McPherson,

about the memory an entire nation has of a year, 1986, that also was rough for me on another continent, the one when my father died stricken by a wasting disease. 8 years later I reviewed Nina's translation for the Nation,

when another college chum published it at Morrow. That review brought me via the Ford Foundation to Ha Noi where I met the novelist and ran around town with her and a student born the same year as Do Hoang Ngoc Anh's narrator whom I married.

The dream of this book seems more real than whole years of my waking life have been. In the dozen chapters I read for an hour in the afternoon, the mother can't cope, as in Huong's novel,

but the daughter cooks for her and feeds her cleverly, valiantly. The grandmother, as in Huong's novel, arrives at the sick bed with food, the resourceful peasant.

The father arrives from the Army to express horror at the privileged medical care his wife enjoys, at the very moment she dies. He is an absent and weak father, as in Huong, and also a cadre like a ghost choking life out of the family, as in her Party villains.

What is more he turns out to be barking, crackers, mad as a hatter, a soldier who builds a sand table in the apartment to figure out his next move. I love that.

The narrator goes to live with her grandmother in the countryside where she learns to gather and store food in secret, survival skills among thieves. This contrasts with Huong's narrator who depends weakly on her overbearing granny.

Then she goes off to a competitive school in the city, arranged by her father, studying as her mother, a reader of novels, never got to. They demand she study ridiculous bullshit but they do demand she learn.

By contrast, Huong's narrator goes to the Soviet Union to work in a wretched factory while hungry and sick, her ghastly Party uncle sucking the life from her to help in his black market trading.

Ngoc Anh's young girl is more robust. 125 pages in, of 280, Renovation is already happier story than Paradise of the Blind, no matter how it ends. Everyone who meets the novelist Huong loves her but no one ever said she was pleased with life.

I may or may not know the novelist Ngoc Anh personally. I think not. I could swear that I have met the very people in the very rooms the novelist describes but you and millions of others might say the same thing.

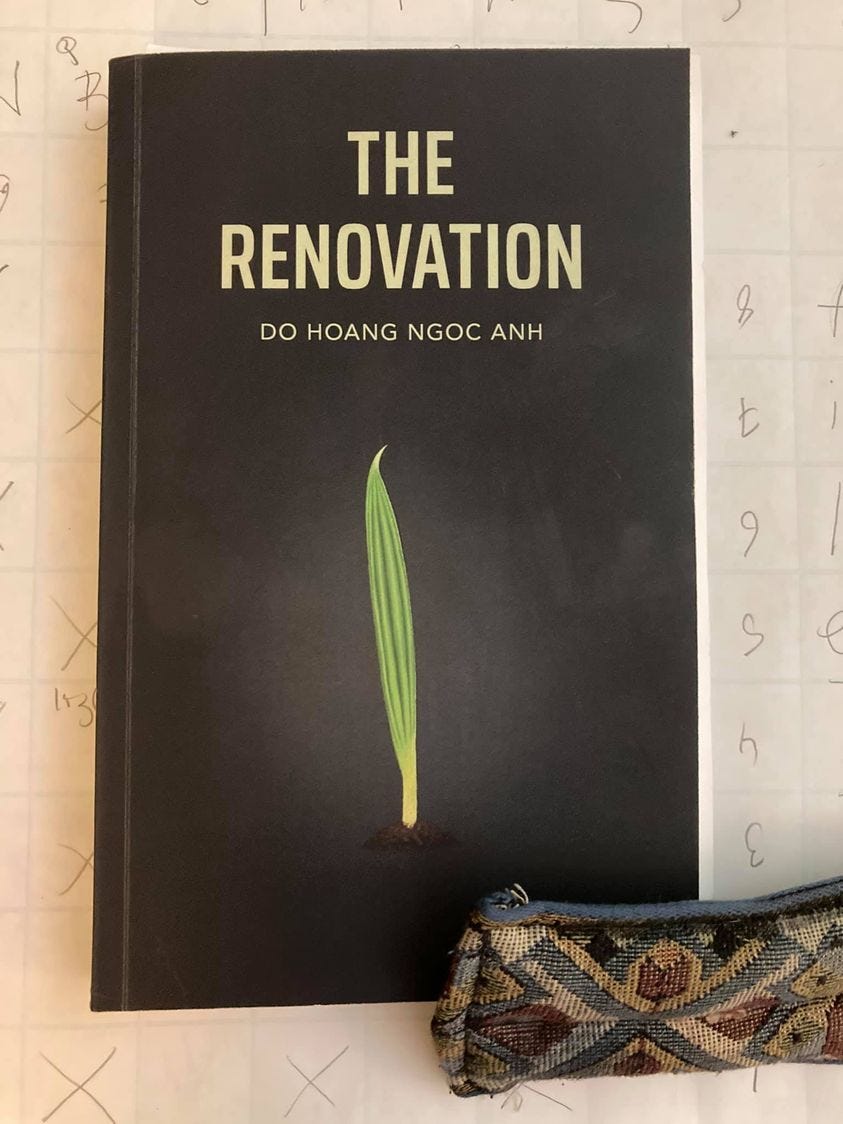

The book conveys hope, the thing with feathers, life's certainty. In chapter 19, The Rice Field, on page 95, I found this passage which sheds light on the lovely cover:

"They said the rice now was just like the girl in the prime of youth, the body transformed from a kid to a woman, all vessels, muscles, skin were changing, developing, full of vitality. The young and fresh rice spread up to the horizon."

This was the fifth of 10 Viet Nam letters so far about The Renovation by Do Ngoc Hoang Anh. The first appeared on February 16, 2022, the second on February 23, 2022, the third on March 12, 2022, and the fourth on April 2, 2022.

After this fifth, the sixth appeared on June 4, 2022. The seventh came on July 16, 2022, the eighth on September 10, 2022, and the ninth on September 14, 2022.

The tenth, on May 29, 2023, was also the first and only Viet Nam letter so far about Đổi Mới by Đô Hoàng Ngọc Ánh.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

Promotional copy:

I married someone who could have written this book. I don't think she did, or any of her friends. But it recalls them all to mind vividly, children born with the unification of Viet Nam in 1976

who entered precocious adulthood just when in 1986 the Secretary General of the Communist Party declared the renovation and opening of the society that brought me there almost 10 years later.

That all is now a Time Far Past (Thời xa vắng) as a novelist of 1986 wrote about his own childhood before the war, married off when Lê Lựu was a small boy. I love that book as I do Do Hoang Ngoc Anh's novel.

Here is a ditty about some time spent reading The Renovation a couple months ago, fourth of the half dozen I have written so far of maybe a dozen total to come. I love the time far past the story conjures

and I love the diction. That woman I married wrote like that. I did light rewrite on her work at her demand until she too could write English with metropolitan authority.

If I brought this book to a publisher for another edition that is what I would have to do. That is, by the way, what people like me do at American publishers for all our native speakers including journalists and professors of English,

because because none of us enjoy world-standard elementary educations. In France the author writes the book and god help any publisher who messes with it over matters of style and taste.

So I don't do that kind of thing. Never, as I love to hear a Vietnamese speaker say in English because it reminds me of my grandmere speaking, never.

Edit the English of a Vietnamese who has been using it in Malaysia through adult life? Why? Do you want to lose the way to a time far past?

Hey, if you like reading me write about the authors of Viet Nam as, you know, people who read and write, please consider signing up for free to say so. It is the one thing I can do

for these people, to read them and write about them such that you read about their work. If it means something to you it means something to them.

Please consider patronizing all this reading at $50/year or subsidizing the whole project at $250/year. The war machine of the United States encourages you by deducting your gift from your income before tax.