It’s a short story about walking off the job into life. John Updike was a contemporary of my mom and dad.

His story is a contemporary of mine, born 1960. All my life, A&P has been something you read if you write stories in English in the United States of America.

You could read this work of art as about becoming a novelist, as indeed John had left the reporting staff of the New Yorker before first publishing A&P in the magazine. The speaker takes off his store’s apron and bow tie then walks out, after his boss shames a teenage muse and her attendants for shopping in their bathing suits.

I call the year of the story at 1951, taking it that the 19 year-old speaker is of the same vintage as the author, born right between my parents in 1932. No one yet knew in 1951 that we all were sitting on a rocket of 20 years’ prosperity for workers.

John and my parents had arrived in the world at the bottom of our great depression, when giving up any employment was brave in the sense of crazy. When A&P appeared in 1961 it was still foolish to quit a job.

You can read the story as looking back from 1961. But in the 10 years back to 1951 such prophets as Paul Goodman already had published books about how alienating it was that all any man had to do to support a family was to show up at 9 and stay until 5.

Really. Not only alienating but also oppressive, they argued in books I browsed discarded in used bookstores across the inflation of the 1970s and the recession of the 80s.

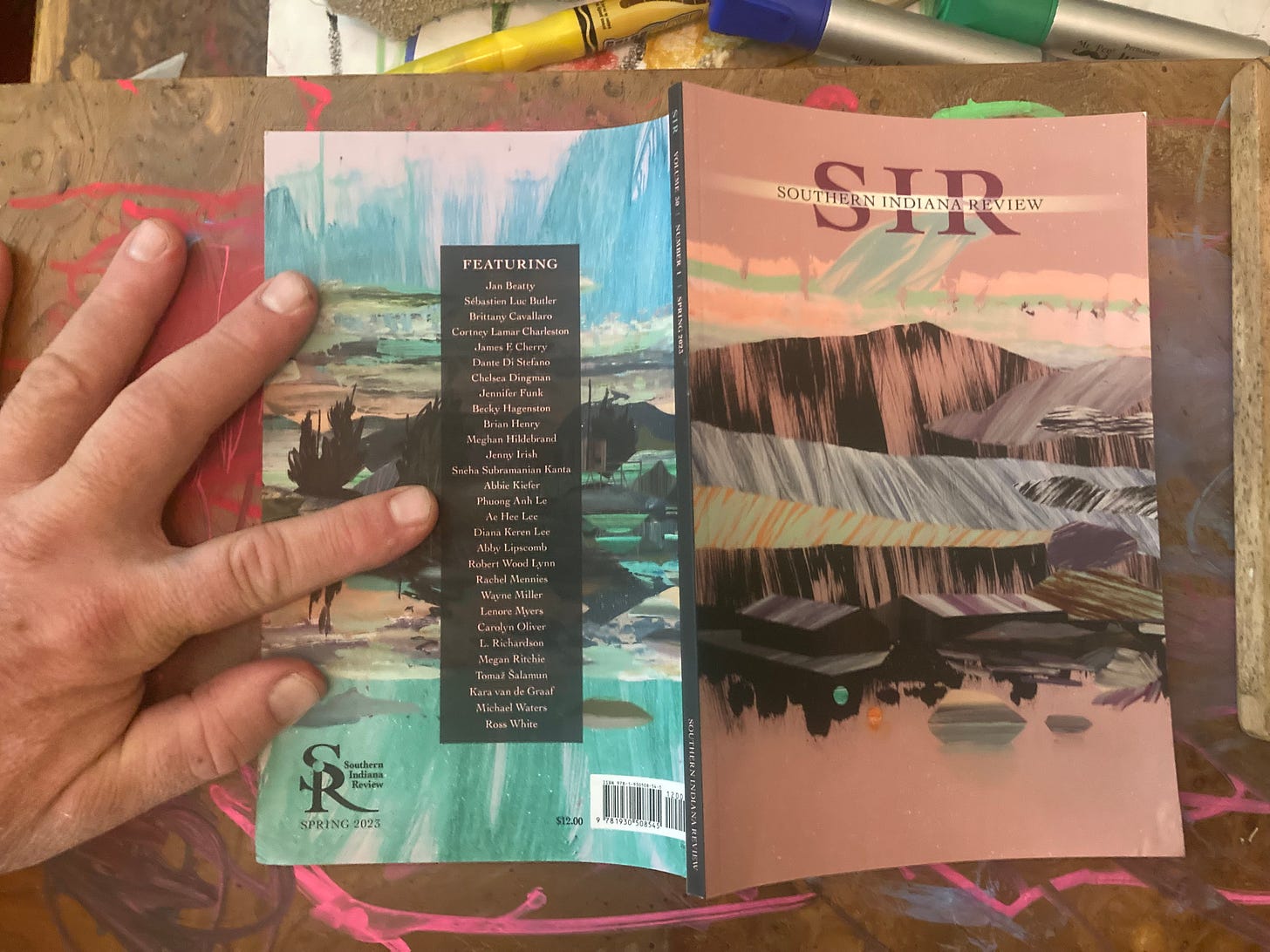

Rainbow is a short story about breaking a rule at work then getting released into life. Phuong Anh Le is a contemporary of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, born the year of unification.

The author and I were contemporaries in Ha Noi across 3 years at the tail end of renovation, 8, 9, and 10 years after the Vietnamese Communist Party had in 1986 called on society, especially writers, to innovate and reform. When we met she was 19 like the clerk telling his story in A&P.

At 21 she flew off to the big show. She trained as a diplomat in New Jersey and lawyer in New York City then as a writer on visits to the mountains west of here in North Carolina while she worked around the world.

Phuong Anh is as cosmopolitan as may be in English. 30 years later here she is with a sophisticated fiction.

Her story is twice as long as John’s, by and about middle age rather than youth, set in a woman’s world of work, in the home as well as at the hotel cleaning rooms. The other focal character is a man, American, Vietnamese, come to stay at the hotel.

It is 1994. He is 49, born with the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam in 1945.

He fled with his family south to the plain Republic of Viet Nam in 1954. We don’t hear that he is one of the Roman Catholic refugees much publicized by our Central Intelligence Agency that year but that his father was a doctor.

1954 was the year the Vietnamese Communists cracked down on the educated, including physicians and surgeons, whom our CIA ignored. Dad died of a stomach ulcer 20 years later in defeat at Saigon in 1976.

The chambermaid is 35. That is the first fact in the story, beginning the second sentence, after reporting her mood in the opening line.

We were born within 12 months of one another. We were about the same age in the same Ha Noi.

Ages 5 through 13, she would have had a front row seat in her home village just across the river for the air war of the United States of America on the republic at Ha Noi. That doesn’t come up in the story.

She was 16 for unification of Ha Noi with Saigon then spent her first 10 years of adult life in the famine after victory, as goes without saying. Some year after 1986, when private businesses opened again and the borders welcomed guests from all quarters, she struggled for 2 years to find her job at the hotel.

I pulled all that together for myself starting from that second sentence. It’s background, it’s there, but the author does not give exposition.

Phuong Anh tells rather how this historically specific woman had an affair with an uprooted man that dislodged her from an arrested life. The Rainbow of the title first comes up when the American Vietnamese tells the woman of the Golden Gate bridge, contrasting it to the old French bridge out of Ha Noi.

Like a rainbow, he says. He is speaking of its arc, as in arc de ciel, that spans the Golden Gate where so many have come from Asia to our beautiful country chasing a pot of gold.

Over the course of their affair the woman crosses her plain straight French bridge back and forth from home to work, from dependent father and brother to lover. She changes her route one day to cast an eye on the ornamental lake bridge downtown, which does arc.

She sees rather than a rainbow a woman’s eyebrow, arch. She has it mind again in the final paragraph, right after getting fired.

That Rainbow is the eyebrow of the lake, she says, the eye of the city. I don’t know what that means yet either.

Rainbow is literature, something an adult may read again and again as we age. John Updike’s A&P is a school piece because it takes you along a clear story arc, easy to learn once and teach over and over again.

A young man grows toward reality by making a romantic decision. Rainbow is the more developed tale.

We hear it from 3 people, who speak 2 languages, man and woman and author all much older than the supermarket checkout boy and his author, in a history we may read should we want to work it out.

John Updike was a stage hick, a small town Pennsylvania boy writing from his small town Massachusetts office, about hicks, to all the hicks who flocked to New York City or read the New Yorker in Peoria in that American century. None of that is my story.

The Rainbow is. I have read it many times already.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

.