It is something we used to say in the middle of last century to preface a statement of resistance against one man one vote and in favor of segregated neighborhoods and schools. Over the third quarter of the century we started saying it to make fun of those unaware that we still led whites-only lives.

That was me, born in New Haven in 1960 and growing up at Woodbridge, Connecticut until 1975, in apartheid more profound than the Union of South Africa. In my home town we didn’t even have black help. No bus line, and close police supervision of anyone on foot from the ghetto just south.

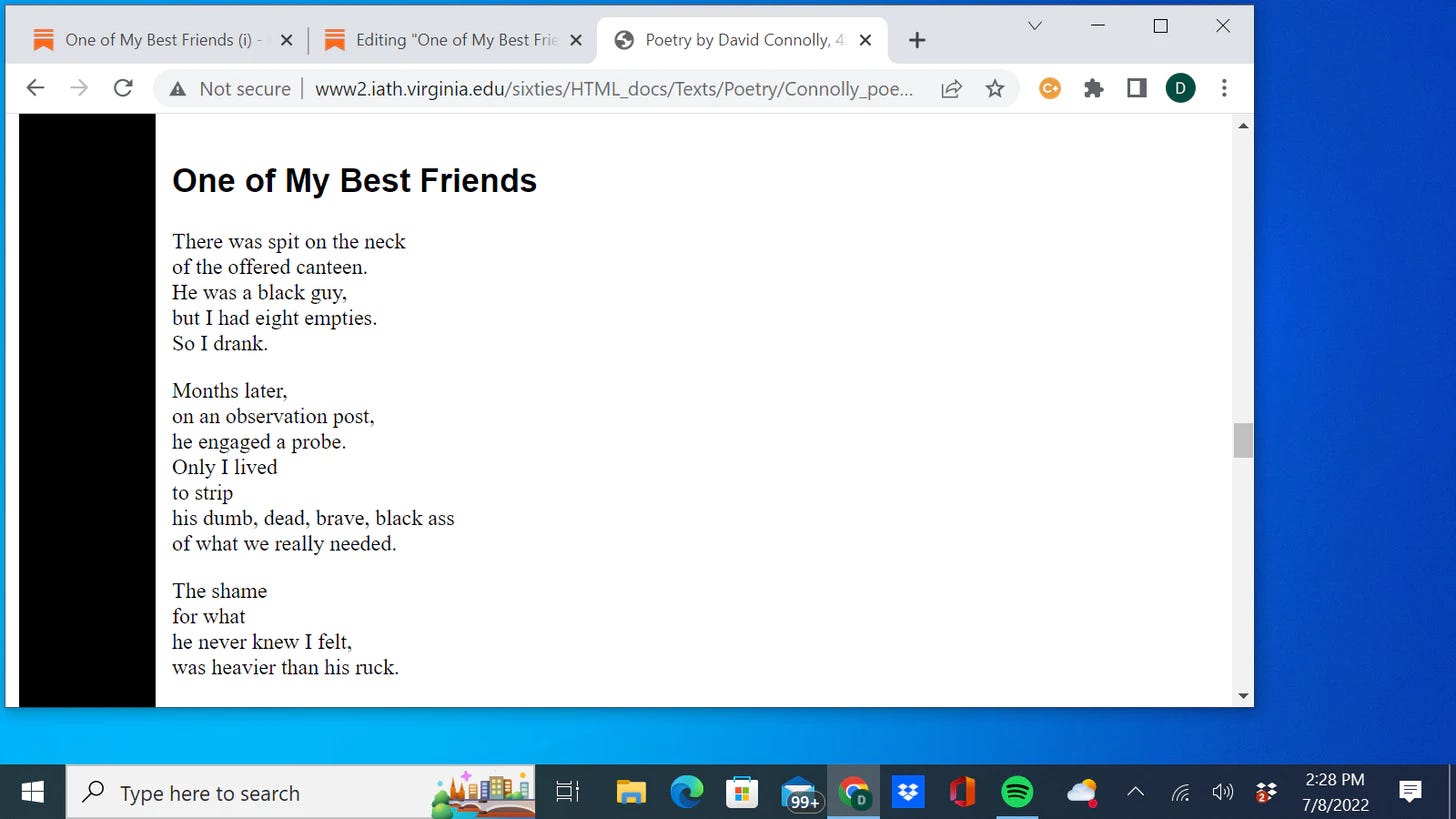

The poet David Connolly is 10 or 15 years older than me from South Boston, Massachusetts, not so much apartheid then as all one vast family. They made the national news over the 1970s resisting integration in open volkisch terms, not with hypocrisy as in the joke of this poem’s title.

In the most unattractive manner possible they made the hard argument that those the joke does apply to used the people of South Boston to right the wrongs of a society led by those who might indeed meet some black Americans only in a service or token capacity.

Those same leaders also sent young David over to fight the People’s Army of Viet Nam. The young man joined what was and remains the most integrated institution of the United States, our Army. Well, our Air Force, founded after integration, might have afforded even greater opportunities for moral reform.

He might then have learned technical skills from highly-trained black airmen. They would not have sent the poet out to kill men trying to kill him with a rifle. On the other hand he might never have grown thirsty enough at an air base to swap spit on a canteen from a brother.

I hope I need to explain today as we approach the second quarter of this century that a white soldier from South Boston back then might refuse to take water from a black one out of embarrassment in front of his friends, fear of cooties, or plain poison hatred. Now, had David come from Boston in the South rather than South Boston,

from Boston, Georgia or Boston, Virginia, he might not have thought twice. Down South in those days boys black and white grew up together and sometimes remained intimate, unequal friends all life long. Often the mother of one of the black boys raised the white ones.

It didn’t pay much but it bought the whole family protection. Maybe David’s brother in the Army came from those relations to white men. Maybe he was just a decent human being. He died at his post out in front of the line, listening and watching for the enemy coming in to learn how to kill those dug in behind.

When they come you can hide and quietly radio in. You can run. You can also blow your mines and shoot at them so they overwhelm you with fire, a patrol from a company running over a few guys in a hole in the ground.

The flash and bang of murder alerts your friends as the whole conduct of your life has lifted them up, for instance this poet David to sing his psalm:

This was the second Viet Nam letter of 3 so far about One of My Best Friends by David Connolly. We sent the first on July 6, 2022 then the third on May 8, 2023. We have posted 1 only on his poem Thoughts on Monsoon Morning, on July 20, 2022 and on the poem Why I Can’t, on August 3, 2022.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

I understand this one. Good!