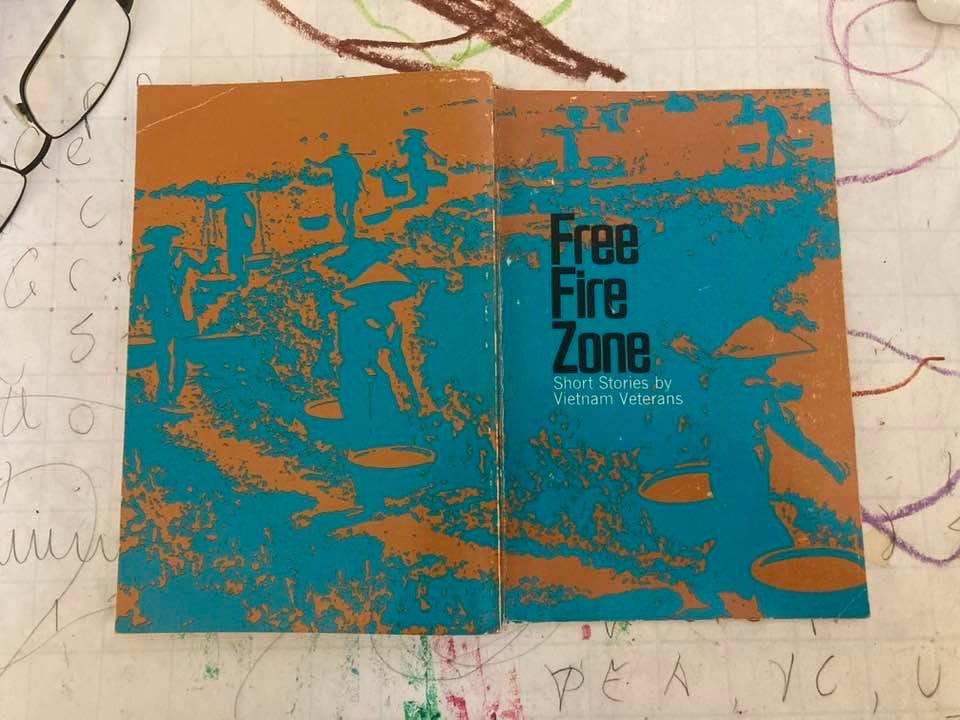

Medical Evacuation (i) in Free Fire Zone (iii)

from author Wayne Karlin and fellow editors Basil T. Paquet and Larry Rottmann at 1st Casualty Press

Medical Evacuation sketches in 3 pages a helicopter flight from Danang and retrieval from Dong Ha of United States Marines wounded at Operation Hastings in 1966. The author was born in 1945 when Marines had 2 more months to fight in the Pacific and no helicopter had yet rescued anyone anywhere.

When in 1973 the sketch appeared in the collection Free Fire Zone from Viet Nam veterans nobody knew that Saigon would fall in 2 years. Back home medical evacuation was an emergency procedure, not yet an air taxi for hospitals, and to speak of medevac in civil life was an affectation.

The sketch is a message cast in a bottle long ago on the currents and tides. Who from? The byline reads Wayne Karlin, one of 3 editors on the title page of the book.

The volume’s index of writers specifies that he is from White Plains and that he fought as sergeant in the 1st Marine Air Wing, in-country at the time of Hastings. The unit is 4 years older than the author. 8 years after he left the 1st flew the last American flights out.

Wayne means wagon. In the United States it is a trucker’s name, as Earl is a leader of men, say outlaw bikers. When Wayne was born, Duke Morrison, named for his dog, for that matter my father’s childhood dog, had been playing cowboys and Marines and soldiers on screen for 15 years as John Wayne,

named to evoke the patriot Revolutionary officer Mad Anthony Wayne by a director who had played a rebel murderer in the movie of Reconstruction, Birth of Nation, the first of many Jim Crow epics where new immigrants learned to get along here among black and white.

Karlin is a name for a place taken as a family name by those wiped off the map there in the 6 years before the boy was born. So, Wayne Karlin the trucker Jew, like Tevye the carter among the Anatevka refugees, like Isaac Babel who rode with the Cossacks making and writing history like an angel in flight.

Standing by for medevacs, he always had the feeling he was being centered in a movie camera.

Well, the author’s name is Wayne and he did ride shotgun on a helicopter 10 years before Apocalypse Now. As a matter of fact the author many more years later played in a Vietnamese war movie.

But this is a literary work, a sketch, a skaz, such as Anton Chekhov and Babel wrote. Such entertainments developed as information in newspapers to become high art in our common century, in our time, as reporter Ernest Hemingway titled his own.

Here we read a character who feels as if he is “being centered in a movie camera.” Not in a movie, a story, but in cinematography. Glimpses as the Imagist poet Hemingway caught before he started telling long stories as a novelist.

But it is later in the century. It is not Ernest Hemingway’s war. Africans did fight in his, as he did not fight at all, but he did not write about them.

Then a full shot of the interior: the black crew chief pumping the A.P.E.

Wayne Karlin notices black Americans in artful delicacy to report the truth. It is 1966, 18 years after the 1948 order eliminating all segregation among men in the armed forces of the United States.

Robert McNamara has only now just begun to draft the most disadvantaged and excluded men to Viet Nam, as if killing people who are trying to kill you is a jobs program. These rather are volunteers, in the first Marine helicopter unit, and that black man is a crew chief. But Wayne dials back the war movie feel-good.

The subtle impact of the scene, no racists in foxholes, by God. No Tuskeegee airmen in this chopper, either. Dark and white meet the grinder together. Of the three casualties the author singles out at Da Nang, one is a black man with a mound of ground red at his neck, the second is a dead blond, and the third is just green.

The gunner imagining the camera eye is a high school graduate. After he returns from his out-of-body experience, watching himself in a camera that wasn’t there, he flies off again, into trivia.

They were flying towards Dong Ha, a flying shovel come to scrape up some of the overflow of bleeding flesh from the Operation. Hastings. Hastily to Hastings, the gunner thought. Where did they get the names?

From 1066 and all that, any high school graduate of the day would reply. 1966 was the 9 hundredth anniversary of the Norman invasion of England and the battle at Hastings.

Then the chopper lands for the wounded. They load, and fly, and off-load as the sketch leaves the artiness and the bookishness of reaction to trauma behind, for the wounds themselves.

The wounded came in through the open rear hatch, touching the sides of the helicopter with gentle, bloody hands. They were already a race apart, consecrated in the eyes of the unwounded, receivers of blows meant for the unhurt. Some whole marines were carrying in those unable to walk and laying them out on the deck. The helicopter was filling up and its blades beat the air insistently as if feeling the danger and straining to go. The interior light dully lit the packed groaning, bodies. The wounded were twisted into one another, holding onto each other, softly bleeding into each other’s wounds. The gunner thought suddenly of a pile of clothes crumpled desolately on a cot, cloth arms and legs locked into impossible positions of sad lifelessness. Pudding, bleeding from between its convulsions.

Back at Danang, unloaded, the gunner grabs a cigarette away from the fuel lines before the next run.

Medical Evacuation is the first of 3 sketches and 2 stories by the Marine, an editor of this collection, who had earned a bachelor’s degree in Israel and a master’s in Vermont after his service. They all follow the same crew. Next up, Search and Destroy.