What’s the big idea?

Ce livre est un ouvrage d’histoire globale sur les transferts dans le monde non européen. Il examine les facteurs et les modalités de la transposition d’une idéologie, le communisme, et d’une modèle politique, le système soviétique, au Vietnam, pays dont l’histoire est marquée par l’influence de la Chine, la domination coloniale française, le combat anticolonial et la guerre froide.

[This book is a work of global history on transfers in the non-European world. It examines the factors and the modalities of the transposition of one ideology, communism, and of one political model, the Soviet system, to Vietnam, a country whose history is marked by the influence of China, French colonial domination, anti-colonial struggle, and the cold war.*]

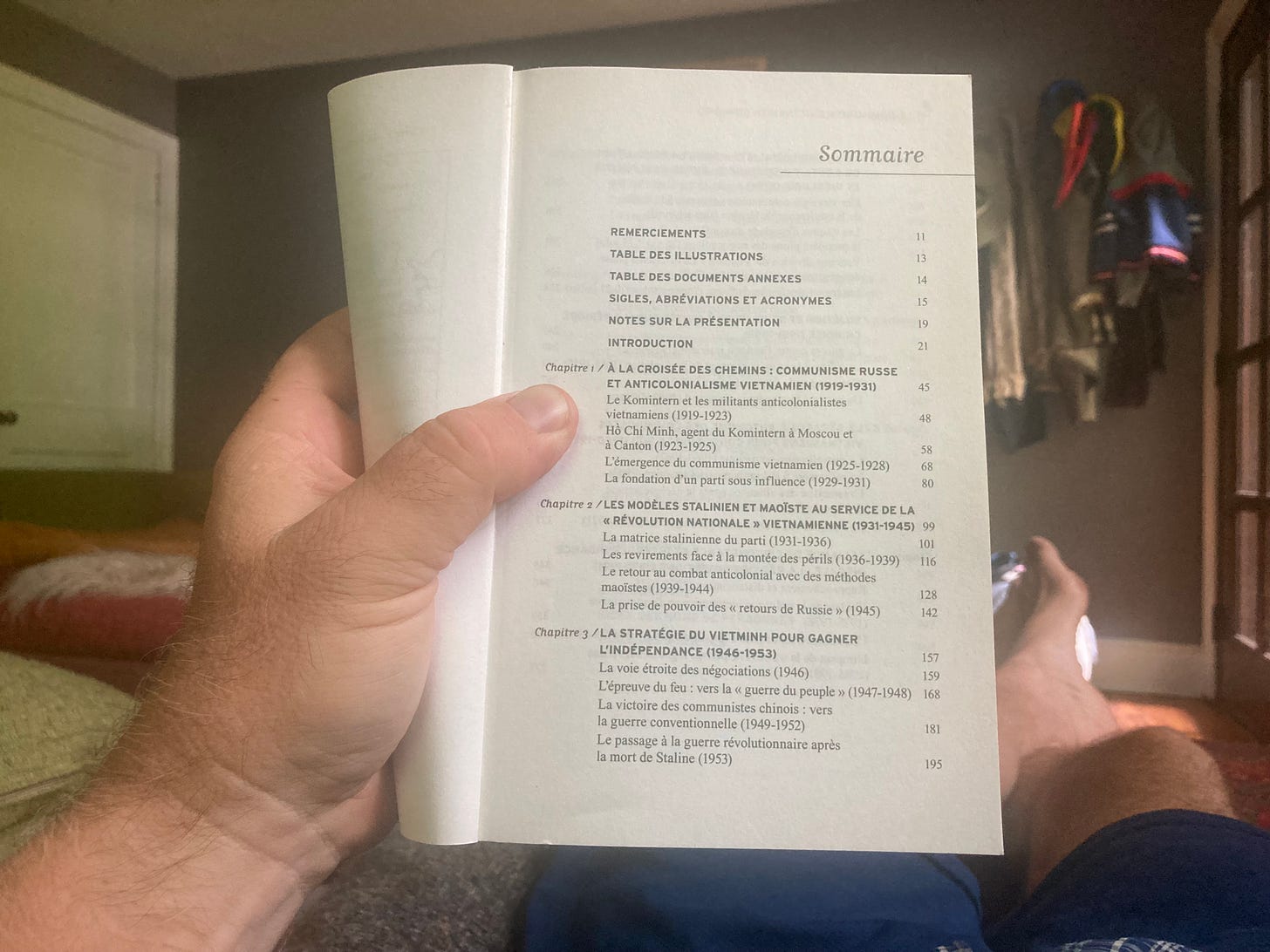

Les trois premiers chapitres s’étendent de la création du Komintern, en mars 1919, au lancement de la réforme agraire en 1953.

[The first three chapters spread from the creation of the Comintern, in March 1919, to the launch of agrarian reform in 1953.*]

Le chapitre 1 relate les effets d’une rencontre a priori improbable, celle du communisme bolchevique russe et de l’anticolonialisme vietnamien, au début des années 1920. Il souligne le rôle fondateur de Hồ Chí Minh, séduit par les positions anti-impérialistes de Lénine dès la fin des années 1920.

[Chapter 1 relates the effects of a meeting, improbable a priori, that of Bolshevik Russian communism and Vietnamese anti-colonialism, at the start of the 1920s. It underlines the role as founder of Ho Chi Minh, seduced by anti-imperialist positions of Lenin from the end of the 1920s.*]

Le chapitre 2 décrit les mécanismes de diffusion des techniques de subversion bolcheviques au Vietnam du début des années 1930 à la dissolution du PCI, en novembre 1945. Les communistes vietnamiens se servirent des modes d’organisation staliniens, puis des théories de la guerre Maoïstes, pour renverser le régime colonial et conquérir le pouvoir.

[Chapter 2 describes the mechanisms of diffusion of Bolshevik techniques of subversion in Vietnam from the start of the 1930s to the dissolution of the Indochinese Communist Party, in November 1945. The Vietnamese communists made use of Stalinist modes of organization, then of Maoist theories of war, to overthrow the colonial regime and take power.*]

Le chapitre 3 s’intéresse à la stratégie du Vietminh, d’abord pour conserver le pouvoir, puis pour gagner définitivement l’indépendance nationale. Il montre pourquoi l’influence soviétique s’effaça pendant la guerre d’Indochine au profit des Chinois.

[Chapter 3 takes an interest in the strategy of the Vietminh, at first to hold power, then to win national independence definitively. It shows why Soviet influence effaced itself during the war of Indochina to the gain of the Chinese.*]

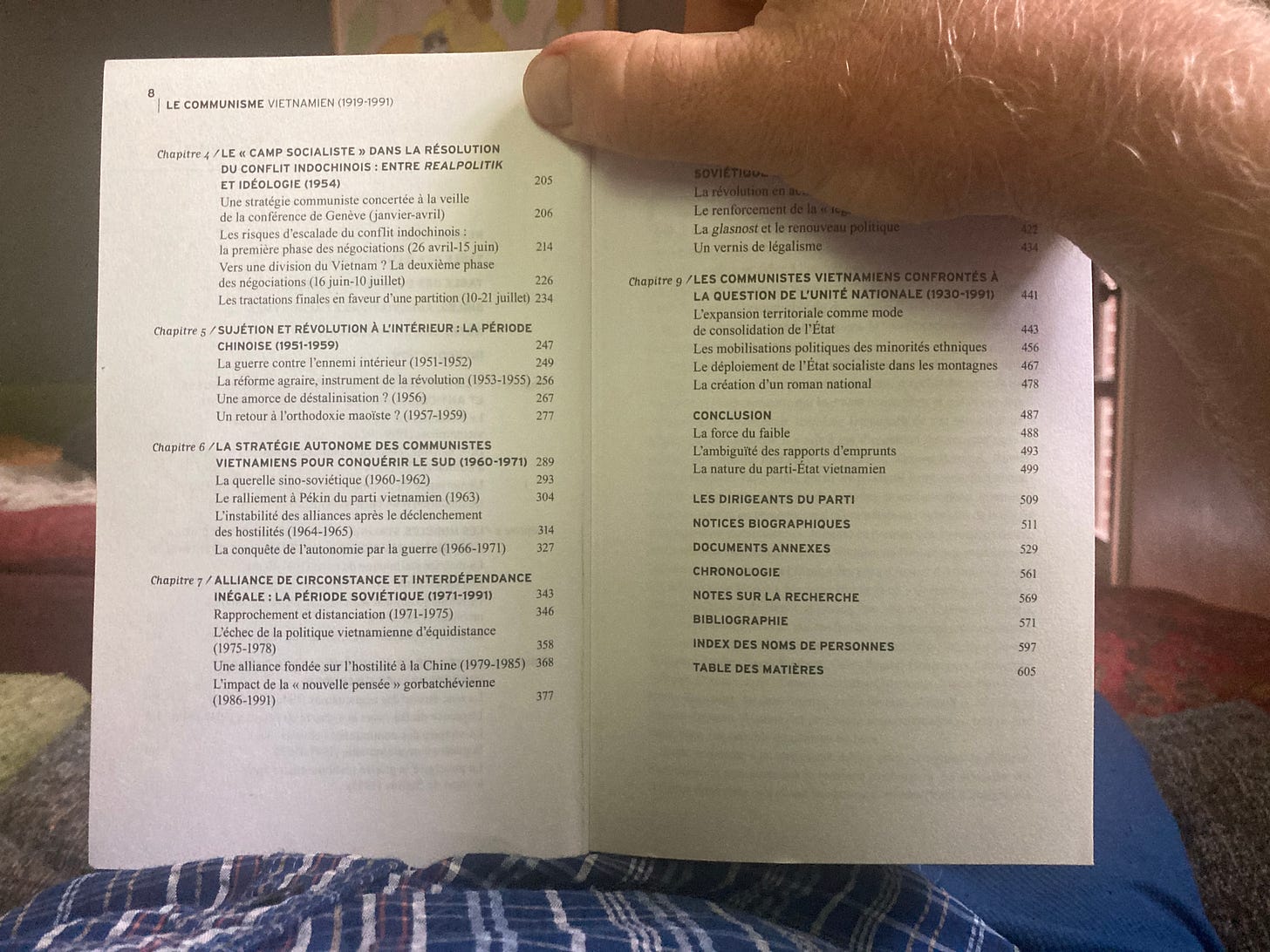

Les quatre chapitres suivants s’intéressent au poids des relations internationales dans le développement du communisme vietnamien. Ils soulignent l’impact de la guerre froide et des relations triangulaires entre Hanoi, Moscou, et Pekin sur l’évolution de la stratégie révolutionnaire, de la politique étrangère et de la politique de réformes sociales du parti-État vietnamien, de la fin de la guerre d’Indochine à la effondrement de l’Union soviétique.

[The following 4 chapters take an interest in the weight of international relations in the development of Vietnamese communism. They underline the impact of the cold war and triangular relations between Hanoi, Moscow, and Peking on the evolution of revolutionary strategy, foreign policy, and the Vietnamese party-state’s policy of social reforms, from the end of the war of Indochina to the collapse of the Soviet Union.*]

Le chapitre 4 met en lumière le rôle du “campe socialiste” dans la négociation des accords de Genève sur l’Indochine qui sanctionnèrent la partition du Vietnam. Les ministres des affaires étrangères chinois et soviétique incitèrent les dirigeants communistes vietnamiens à accepter cette division territoriale, ainsi que l’évacuation des troupes du Vietminh du Laos et du Cambodge.

[Chapter 4 brings to light the role of the “socialist camp” in the negotiation of the Geneva accords on Indochina that sanctioned the partition of Vietnam. The Chinese and Soviet ministers of foreign affairs pushed the Vietnamese communist leaders to accept this territorial division, as well as the evacuation of Viet Minh troops from Laos and Cambodia.*]

Le chapitre 5 présente les mécanismes de diffusion du modèle révolutionnaire chinois au Nord-Vietnam dans les années 1950, ainsi que les conséquences du XXe congrès du Parti soviétique et du mouvement des Cent fleurs chinois sur le cours des réformes socialistes au Nord-Vietnam. Hanoi commença à s’émanciper de la tutelle des Chinois, en prenant à leur insu, en janvier 1959, la décision de relancer la guerre et de redonner la primauté au combat pour la “libération nationale’, alors que les États-Unis renforçaient leur présence militaire au Sud-Vietnam et au Laos.

[Chapter 5 presents the mechanisms of diffusion of the Chinese revolutionary model to north Vietnam in the 1950s, as well as the consequences of the 20th congress of the Soviet party and the Chinese movement of 100 flowers on the course of socialist reforms in north Vietnam. Hanoi began to emancipate from the tutelage of the Chinese, in taking without their knowledge, in January 1959, decisions to launch war again and and give priority to the fight for “national liberation,” when the United States reinforced their military presence in south Viet Nam and in Laos.*]

Le chapitre 6 présente la stratégie mis en oeuvre par Hanoi pour renverser le régime sud-vietnamien et réunifier le pays du début de la querelle sino-soviétique en 1960 au rapprochement sino-américain en 1971. En dépit de leur dépendance économique et militaire, les dirigeants nord-vietnamiens firent preuve vis-à-vis de Moscou et de Pékin d’un grande indépendance d’esprit, d’une méfiance toujours plus grand et d’un art consommé de la dissimulation.

[Chapter 6 presents the strategy applied by Hanoi to overturn the south Vietnamese regime and reunify the country from the beginning of the Sino-Soviet quarrel in 1960 to the Sino-American rapprochement in 1971. In spite of their economic and military dependence, north Vietnamese leaders demonstrated vis-a-vis Moscow and Peking a fine independence of spirit, both thought and will, a distrust even greater and a consummate art of dissimulation.*]

Le chapitre 7 met en exergue la volonté d’autonomie des communistes vietnamiens et les limites de l’influence soviétique au Vietnam du début des années 1970 à la dissolution de l’Union soviétique en 1991. Après la victoire d’avril 1975, Hanoi mena une politique d’équidistance entre Moscou et Pekin.

[Chapter 7 spells out as on a coin the autonomous will of the Vietnamese Communists and the limits of Soviet influence on Vietnam from the 1970s to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. After the victory of April, 1975, Hanoi led a policy of equidistance between Moscow and Peking.*]

Les deux derniers chapitres constituent un essai de définition du communisme vietnamien suivant deux angles de vue complémentaires: la construction du communisme et la construction nationale.

[The two last chapters constitute an attempt at a definition of Vietnamese communism following two complementary perspectives: construction of communism and national construction.*]

Le chapitre 8 porte sur l’évolution des modes de légitimation et d’exercice du pouvoir après 1975. Il expose les ressorts de la terreur révolutionnaire dans l’immédiat après-guerre, les efforts engagés, a partir du début des années 1980, pour rationaliser (et renforcer) le contrôle social en s’appuyant sur la loi, puis, à partir de 1986, pour promouvoir une politique de “renouveau” et de “transparence.”

[Chapter 8 bears on the evolution of modes of legitimation and the exercise of power after 1975. It lays out the springs of revolutionary terror immediately after the war, the efforts engaged, from the beginning of the 1980s, to rationalize and reinforce social control while leaning on law, then, from 1986, to promote a policy of “renovation” and “transparency.”*]

Le chapitre 9 se penche sur l’évolution du discours et des pratiques en matière de construction national à travers notamment l’exemple du traitement des minorités ethniques montagnards. À partir de 1960 et plus encore après 1975, le parti-État s’appuya sur la colonisation vietnamienne et la sédentarisation forcée des minorités nomades pour étendre sa souveraineté dans les regions reculées du pays.

[Chapter 9 looks into the evolution of discourse and practices in the matter of national construction across notably the example of the treatment of ethnic minorities of the highlands. From 1960 and more yet after 1975, the party-state leaned on Vietnamese colonization and forced sedentarization of nomadic minorities to extend its sovereignty in the remote regions of the country.*]

[*This is not a translation into literary English. It instead mixes American and British usages to follow the French word for word, in order, except for placing modifiers before the modified, in the same part of speech, in the same constructions. In schools we call this a trot.]

[*Beware. English versions belong wherever at all possible to the common administrative lexicon of the 2 languages. Sometimes the French word means the exact same thing in English, sometimes not quite. Twice I provide a gloss in italics, once on evergue, an expression in French only, and once on esprit, whose meanings are exact and forceful in French but vague and weak in English.]

[*I have not followed the author’s capitalization and spacing of words, or adapted them to any prescribed English style. This is not a translation. This is a trot. You jog back and forth between my walk and her canter.]

This is the sixth of 6 Viet Nam letters on Le communisme vietnamien by Céline Marangé. The first begins with how I found the book.

The second letter judges the book by its cover.

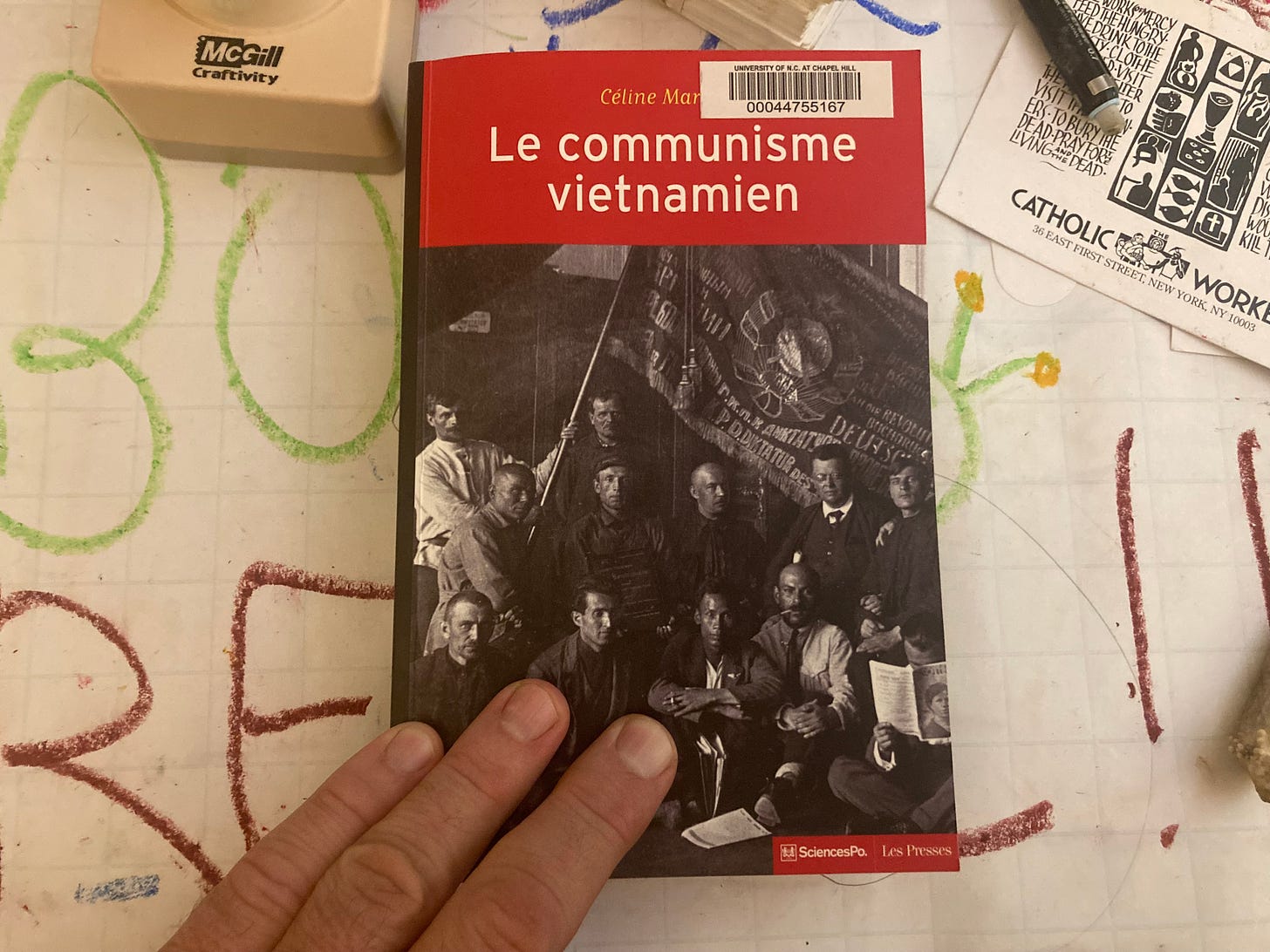

The third letter bears down on the Vietnamese in the photograph.

That sharp dresser on the cover by my middle finger. That man, in the tones of a bourgeois in Ha Noi speaking of an arriviste from Nghe An. Who in the world?

My fourth letter addresses the back of the book.

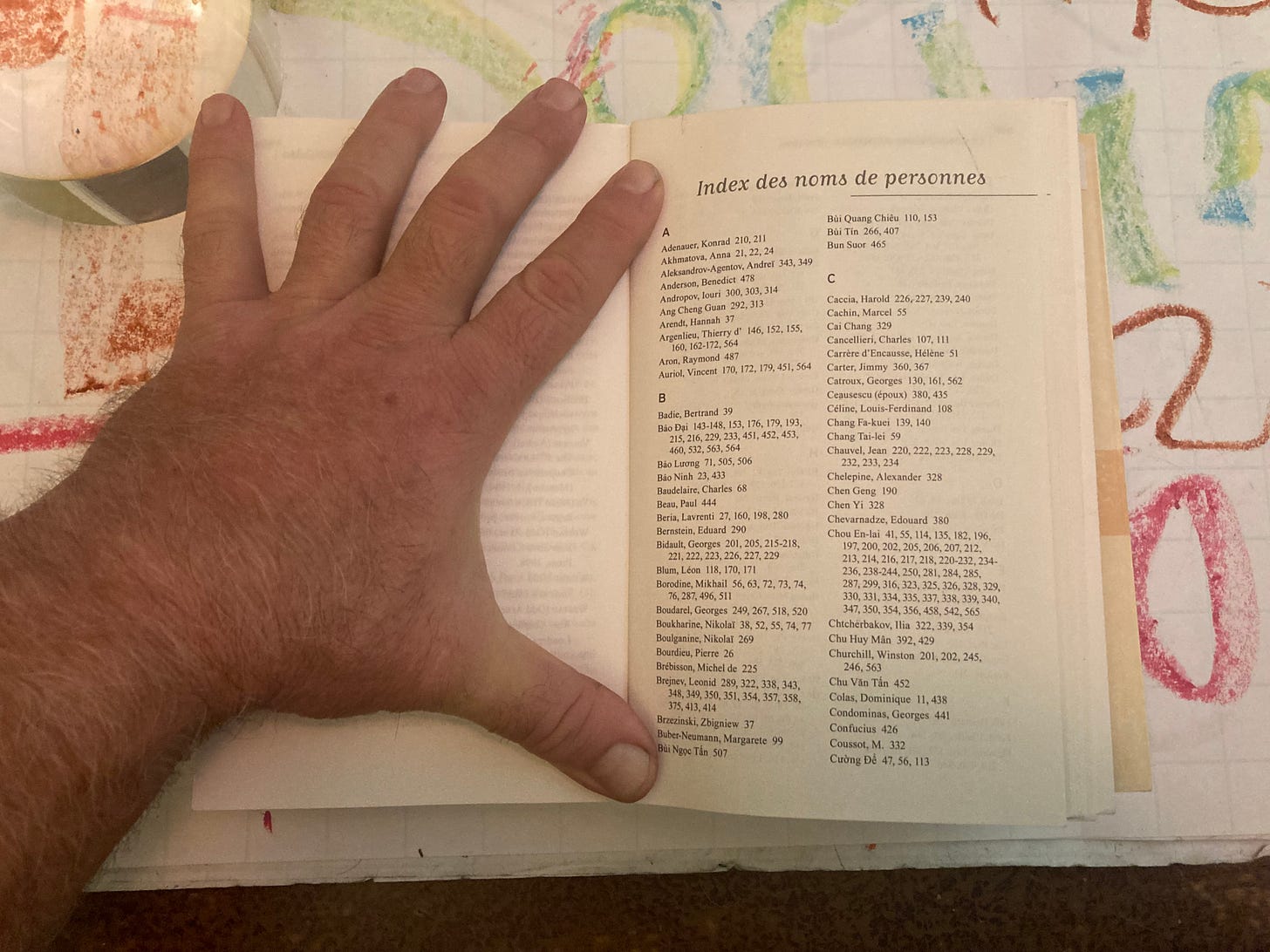

Index. Point with the index between a thumb and middle finger to the index of a book. It indicates the contents and points you inside.

The fifth letter at last reads Céline Marangé’s analytic narrative. Well, the first paragraph of her introduction. Small bites. Long chew.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.