I was the hired man caring for 20 thoroughbred mares, their stallion, and foals on a farm where I slept in a hayloft 10 miles north of our place now in Durham. I also audited intellectual property in mergers & acquisitions, day labor at the office of that month’s target.

So I had a tan you could call ranch manager. Radiation burns around the eyes, light red neck, pepper and salt hair on tan forearms. 50 and fit but not a gym rat or a dawn-to-dusk laborer. One month I found myself in line to board a Southwest flight. There I was, shoulder to shoulder with myself,

recognizing myself, walking in front of myself then sitting down beside myself in the first two open seats. We were flying from Raleigh, not far from where Fort Bragg where the Special Forces train, to Nashville, not far from Fort Campbell from where the paratroopers deploy.

I knew who my double was. I knew he was mistaken about what I did for living. How are you, he asked, where are you going? I can’t tell you, I said, embarrassed. I dislike letting other people take me for a soldier,

but I couldn’t just tell him what I was really doing on that flight. I had agreed never to speak of it in any way. Every time I have signed a non-disclosure agreement it has bit me in the ass just this way. Risk management, I offered.

A cloud passed over his face as to say can’t you even bother to lie in an entertaining way then I said I am a Viet Nam country specialist. He lit up. We had a nice long chat on the flight to Nashville, capital of the Volunteer state where they had a civil war within our Civil War. So we keep a fort there.

The United States Special Forces know all about Viet Nam specialists. We began together in the war for the world as the fellows who guided their language study at the hands of native speakers, before the soldiers jumped into the Japanese empire to gather information and send downed pilots home.

We ourselves lectured the paratroopers on the people they would meet, on the terrain. After victory when the United States carved up the world up in areas of contest with rivals and influence with allies those areas became our areas of study. For instance, Southeast Asia studies.

I first heard of Loyd Little after he died in a book I had owned for 30 years but in life we were neighbors in the same small town, just north of our common university, full of Southern novelists working at that university who know me who must have known him. But he was another close double,

that is, like the man also flying to Nashville, not my double at all. I could have played him on tv as he could have played me, each of us knowing the other well from the outside. Indeed, his second novel is all about area studies.

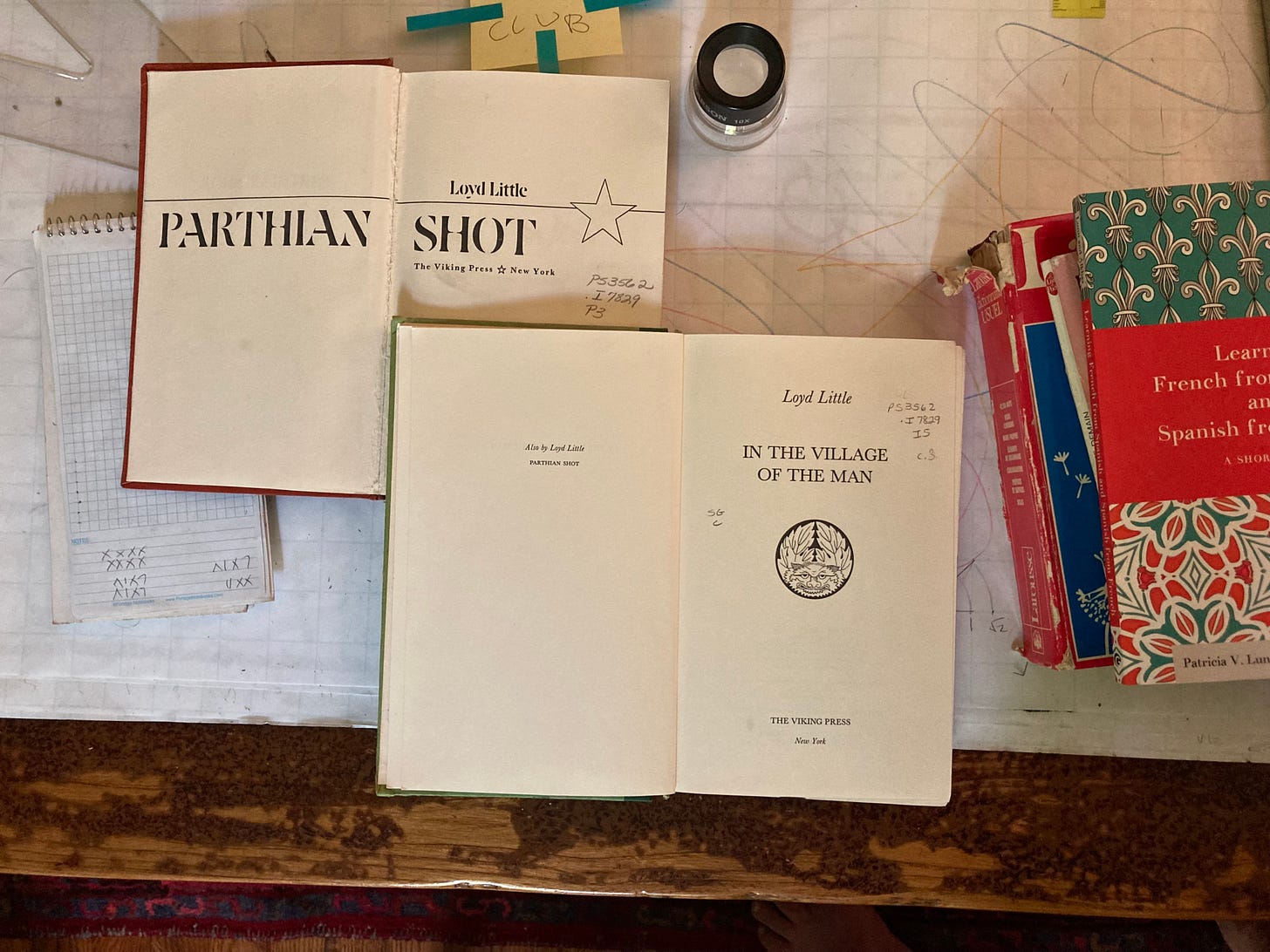

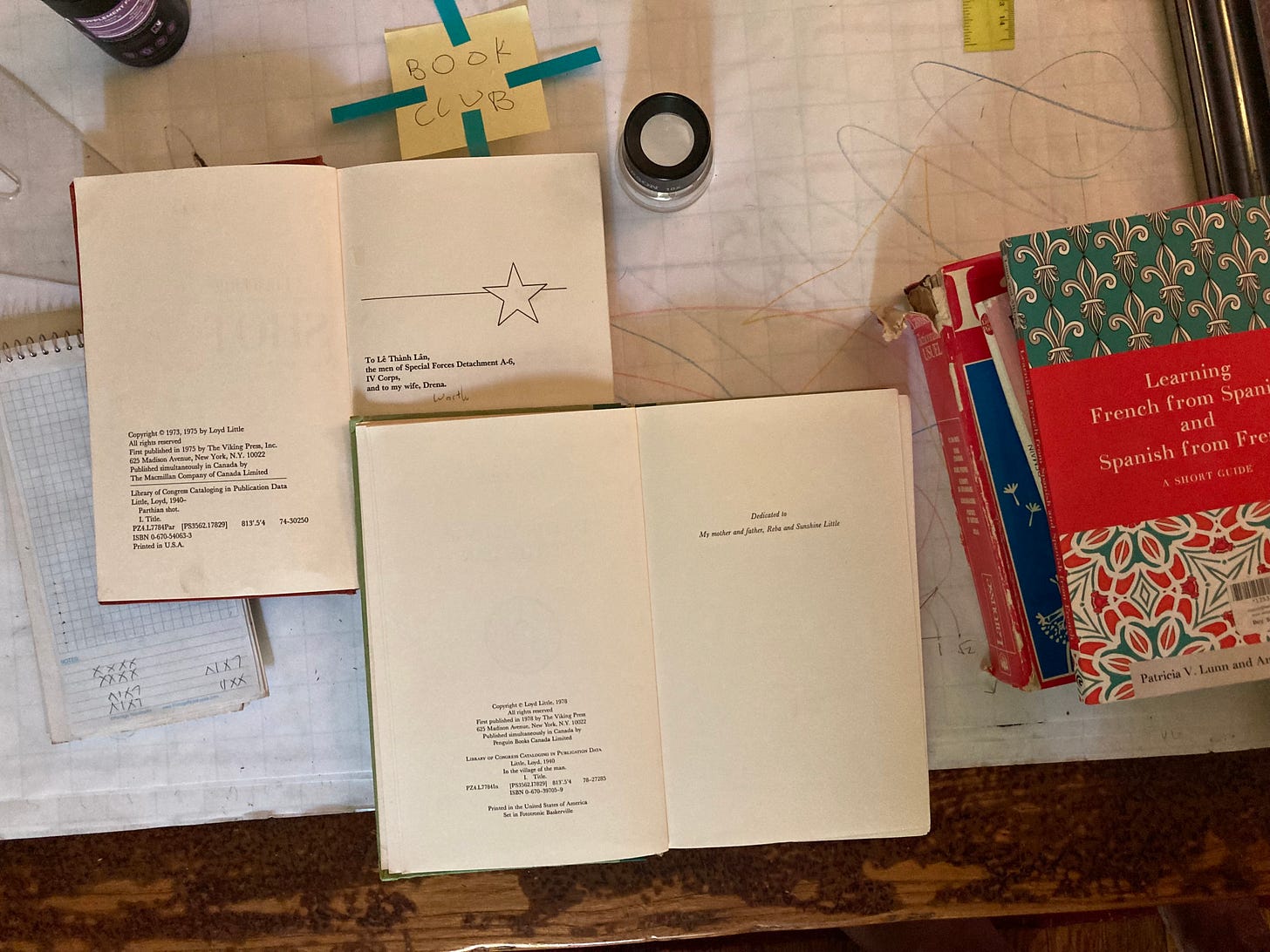

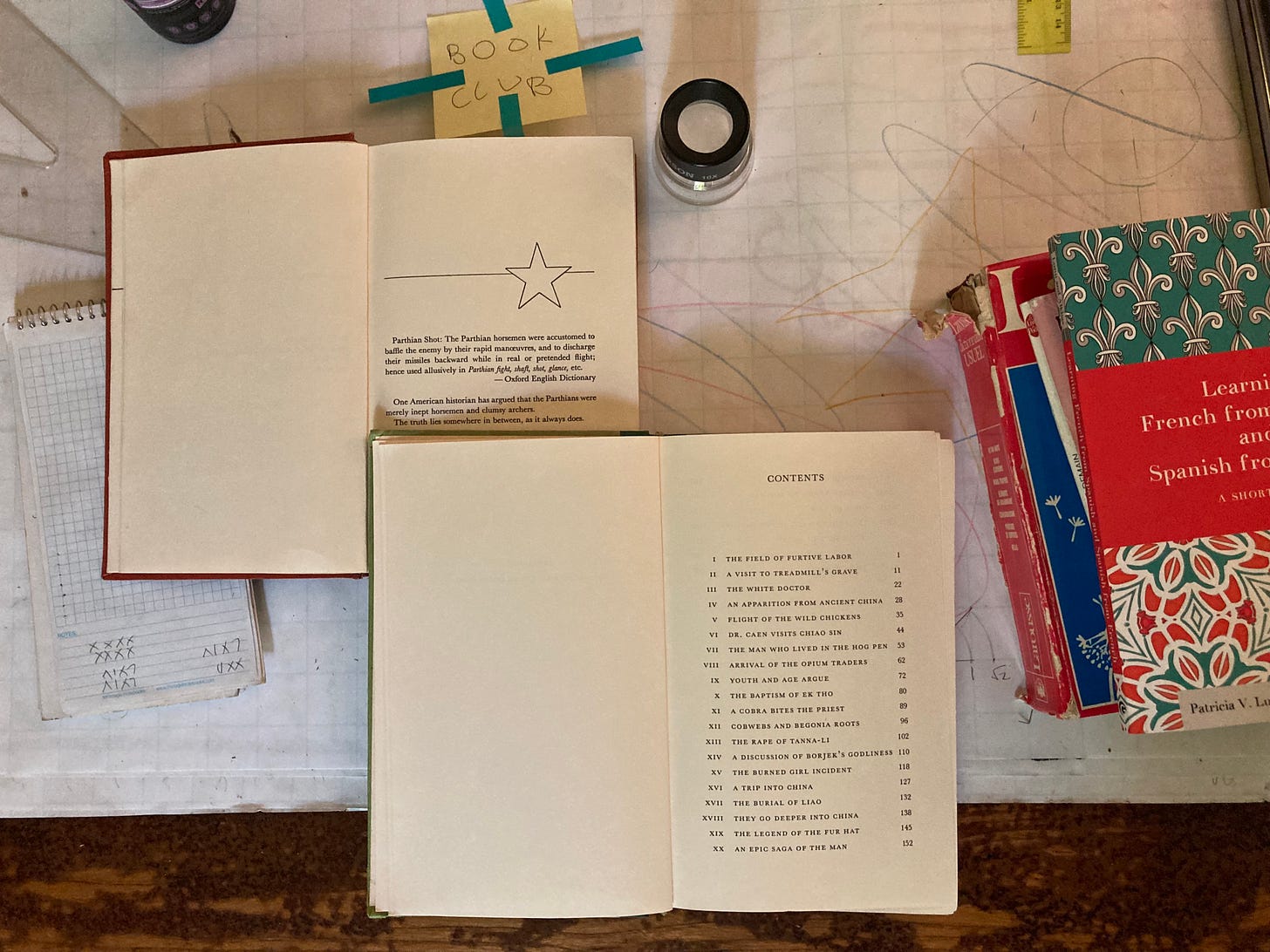

The first one, Parthian Shot, background in these photos, is a comic tale of soldiering, I think from his own work in Cambodia. This second one, In the Village of the Man, foreground, is a funny tale of do-gooders and missionaries and spies in Laos. All of that mountain country is a border area between Thailand and Viet Nam. It is a frontier.

Anna Tsing, my colleague in anthropology as well as area studies, wrote her In the Realm of the Diamond Queen about such a zone at the edge of another Southeast Asian nation, where an odd collection of isolated locals and mad visitors live in their imaginations of some greater world.

I expect that the novelist heard one-third of the characters and details from chatter among friends in the Special Forces who catered to the Central Intelligence Agency at their private party there. I expect he made up a second third.

Since the very presence of the United States in Laos was itself a work of the imagination it would be hard to tell the stray facts from the jeux d’esprit in those first two thirds. The final third, however, is the property of Southeast Asia studies.

The information presented about the hill people of Laos, their languages and livelihood and migrations, their political history, their relations with the dead and the family next door, all are our work. Indeed one vehicle for exposition is a former Special Forces officer recalling his area studies reading.

You can get all that stuff out of our books. Why we write them. We don’t need to yammer at you and leave you with impression that you learned something. You need to learn it. I did do one area studies lecture on slow boat from Cambodia into Viet Nam, just to get back there.

I was terrible. I even brought one of the best Vietnamese authors I know to meet the passengers. They weren’t interested in her either. They wanted someone to tell them all about Viet Nam, as an art historian on the cruise told them all about the fabulous ruins of Angkor Wat.

I am the wrong guy for that job. They were college graduates who go to culture for enrichment. That is not what we in area studies do. You need to study like the paratroopers, then jump. Get to know people and learn how everything you read was out of date or wrong headed.

You need then like the others in the frontier regions to make up a world in your head. Let’s see what old Loyd did not far from me in Hillsborough where I later shoveled shit, watched grass grow, and thought through what I had read and the friends I made around Viet Nam.

This was the second Viet Nam letter of 4 so far presenting the author Loyd Little. The first posted on April 20, 2022, then the third on October 24, 2022, and the fourth on April 17, 2023.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

"You need to study like the paratroopers, then jump. Get to know people and learn how everything you read was out of date or wrong headed." Thank you for providing this mirror that helps me understand my past decades' experience for the first time.