Familial Properties: Gender, State, and Society in Early Modern Vietnam, 1463-1778 (iv)

from historian Nhung Tuyet Tran and Vietnamese studies

“From the fifteenth to the eighteenth century, the Lê, Mạc, Trịnh, and Nguyễn families all claimed the right to govern the Vietnamese-speaking populations of the Indochinese peninsula, and they articulated a governing philosophy that linked political and social order to familial order.”

The clans strove against one another in battle, not in chancery court or in probate. They drafted all the men, not in selective service but in wholesale conscription. They took all the guys.

The clans of Berlin and Paris squabbling over Europe did the same thing 1914-18 to my grandmere’s village, more briefly, but still. Come to think of it Paris then drafted women from Indochine to replace men at her Saint-Parize-le-Chatel and many other spots in deep France.

They all died in the flu at the end of the war for Europe and played their role in the nation of Viet Nam only at home in family altars. But back in the day of Nhung’s book, 1463-1778, the women abandoned in the wars to establish a single familial order of a Vietnamese nation had coped, prospered, and established women’s place in the new public world.

That is what Nhung Tuyet Tran’s book is about. She includes their poetry:

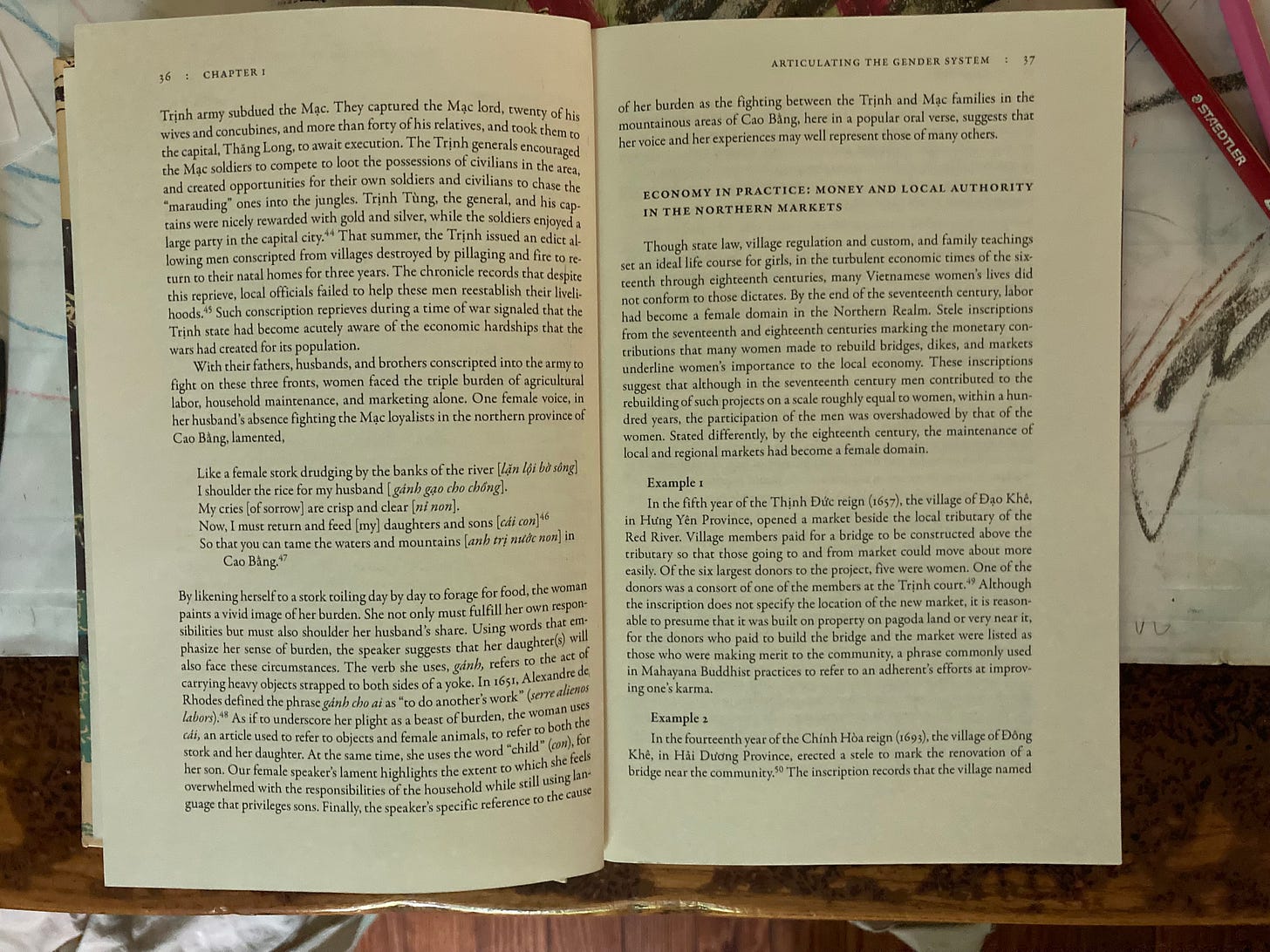

Like a female stork drudging by the banks of the river I shoulder the rice for my husband My cries of sorrow are crisp and clear Now, I must return and feed my daughters and sons So that you can tame the waters and mountains in Cao Bang.

If you read verse in Christendom, which has included Vietnamese speakers since Nhung’s period, these lines recall another shore bird, the pelican, who pierces her breast to feed her young. That is the story anyways

and why you may see a pelican carved on an altar, Mary’s love for Jesus then Christ’s love for Christians as a hen’s for her chicks. Plain old chickens are even more common in that context. It makes me wonder if all these birds also represent women’s role in the European public space.

Look at the right-hand page below, recto, opposite the heron poem, verso, to read Nhung’s argument that over her period in Viet Nam women’s labor and marketing built the public space of the markets, and memorialized themselves there. Not covertly as hens but by name.

Cool.

This was the fourth Viet Nam letter of 7 so far addressed to Familial Properties: Gender, State, and Society in Early Modern Vietnam, 1463-1778 by Nhung Tuyet Tran. It is the first letter with the poem, “Like a female stork drudging by the banks of the river.”

The first letter judges the book by its cover, on March 30, 2022.

The second letter reads the title page, on April 30, 2022.

The third letter discusses Vietnamese women and Southeast Asia in light of the book’s introduction, on June 1, 2022.

The fifth is the second letter to discuss epigraphy from steles women raised in the markets they built, on December 12, 2022.

The sixth is the third letter to show and the second to discuss “Like a female stork drudging by the banks of the river,” on December 15, 2022.

The seventh letter, on March 27, 2023, presents 2 more poems to make the point that the work of history is also an anthology.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.