The author Linh Dinh has chosen poems from each of 7 published volumes of verse. When you do this alive we call that volume selected poems.

Linh calls this 1 collected because he feels that poetry has died in him. The poet Wallace Stevens felt the same way for years, twice.

Each time he later began again. Then as he died he gathered all the published work together as his collected.

His daughter Holly later selected poems for a book like Linh’s. I knew her around books in our native Connecticut as I have known Linh out and about around our literary Viet Nam. Holly, the age of my oldest uncles, died last century. Linh is the age of my next younger brother.

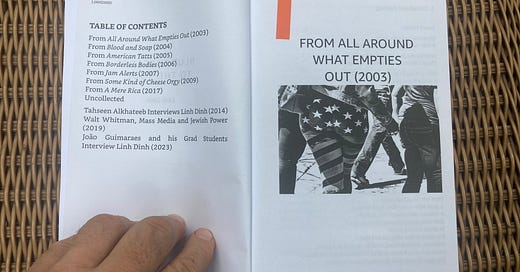

I think Holly and Linh each did a great job selecting. I know that Linh may prove as mistaken about poetry dying as Wallace did, twice. All Around What Empties Out, the title of the first volume the poet has selected from, is his English gloss on the Latin anatomical term perineum.

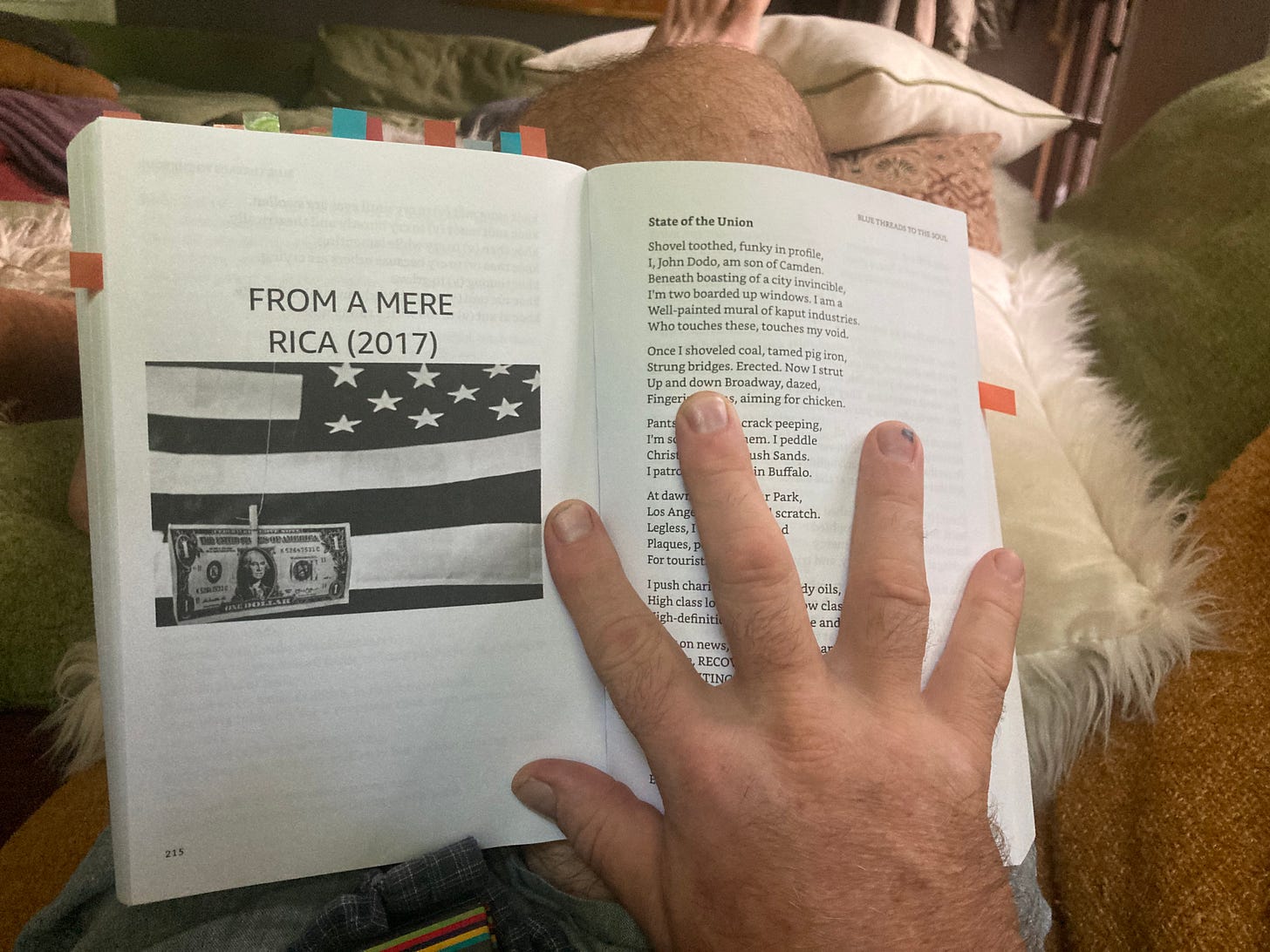

What we here in North Carolina call the taint. It ain’t one or the other. The poet refers to the entire region of the anus, genital organs, and urethra. He illustrates the selection from this first volume with a later photograph of the flag of the United States of America wrapped tight around what empties out.

Get you some.

And yet the water keeps rising, and each year we must raise the floor a little higher, a little closer to the ceiling.

My selection from the first volume, Floods in Quang Ngai, speaks from a house where they keep raising the floor away from each new year’s rising water. Quang Ngai is the province of the village My Lai, halfway between Hanoi and Saigon in their war.

There were floods there before the massacre and indeed the waters have risen since. You don’t have to know that. If you are reading poetry in English you have known forever about the man who rolls a rock to the top of a hill every day until it rolls back down and he begins again.

You don’t have to remember his name right off. You don’t have to know where Quang Ngai is and what we all have done there. Now you know about the people who raise the floor closer to the ceiling after each year’s flood.

Will you forget that?

You cannot understand the story of a youth who falls in love with his own reflection in a spring. Where you are, water does not reflect. Nothing reflects. One’s view of oneself is made up entirely of other people’s slanders.

13 is the 1 poem the poet selected from the second volume, Blood and Soap. He did not illustrate the selection.

I have pulled out the tenth stanza. The 9 before and 3 after address the reader in the second person to narrate inchoate experience of being out of place. The novelist Jay McInerney, my older brother’s age, told his Bright Lights, Big City tale of 1980s Manhattan that way.

You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. By the last sentence Jay’s character and story arc has arrived at integration of self and into society. When his novel came out it was 1 of the most exotic tales I had read, both in origin and destination.

Linh’s stanzas by contrast immediately joined just now those of It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) and Ballad of a Thin Man in my head where those had lodged instantly the years Bob Dylan published them, 1964 and 1965.

You lose yourself, you reappear, in waking details and dream logic condemning the only society there is to join. You hand in your ticket and you go watch the geek. 1 dozen of Linh’s 13 stanzas talk like that, like my voices within.

You let out a high C and touch yourself immodestly (the end of the fifth stanza, top of right page shown.) You smirk at this provocation (the sixth stanza, shown.) You crave a single moment of absolute exposure (the seventh stanza.)

Waking up days later, you are told by a lugubrious dog that he, too, has often slept through the best parts (the eighth.) In the men’s room of a small-town bus terminal, you discover your oil portrait in a trash can (ninth.)

The tenth stanza visits many other people’s story, that of Narcissus:

Nothing reflects. One’s view of oneself is made up entirely of other people’s slanders. If you are reading this you have heard long ago how Narcissus starved staring at himself while his girlfriend echoed helplessly unable to speak of her love. I asked my psychiatrist once if narcissism was my problem.

She replied that it is an issue in the development of the self.

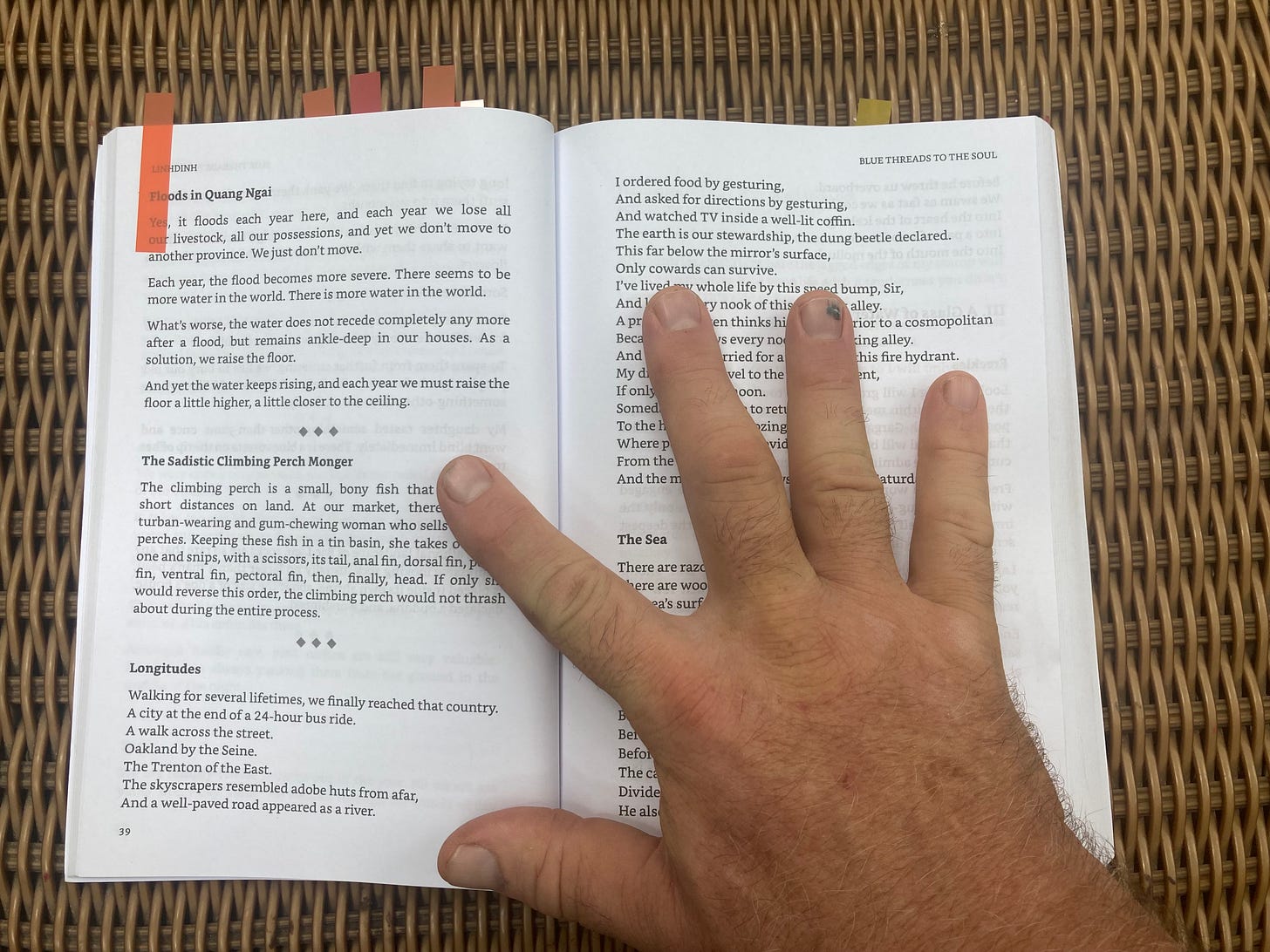

American Tatts

Linh likes local bars where people go to drink. Who doesn’t? I haven’t set foot in 1 since an evening last century when everyone there rose in a body to drag me out the front doors and stomp me in the parking lot. I had been seen talking to a friend of my dead grandparents, a gay man. I got away.

Look at how observed this shot is, and how the poet participates in the life of the bar. I shoot like that in my family after the same 15 years here that Linh has spent on the road among the barflies. If I started snapping candids in a bar faces would freeze and turn away.

I think Linh may have propped up the bar in this very saloon for years before he set out to visit them all, everywhere.

The man on the left stank so much, I had to chain-smoke Lucky Strikes to cancel his funk.

Of all the backslapping drunks I knew in Philly, I’ve always wanted to describe Joe LeBlanc.

I love these portraits. Linh writes from the world of his adult life rubbing elbows and shoulders in the world where generations of my family and no degree of separation among my friends have lived.

I have deliberately spent my adult life distant from booze and cigarettes. Still I like hearing from the old country.

I love that he pays attention to the addicts.

Borderless Bodies

Bodies and borders are all we talk about among my cohort in the human sciences. Just listen to these titles this century from Duke University Press alone, here in Durham.

I have picked only 3 with each, bodies and borders, of many more from this 1 publisher.

Bodies in Formation (Prentice, 2012), Plastic Bodies (Sanabria, 2016), and Infamous Bodies (Pinto, 2020.)

Feminism Without Borders (Mohanty, 2003), The Border Reader (Rosas & Losa, 2023), and Indigenous Peoples and Borders (Lightfoot & Stamatoulou, 2024.)

I have found only 1 book title from here in Durham with bodies and borders both: The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves; How Feminism Travels across Borders (Davis, 2007.) I did find many more than these 3 chapter titles linking both words:

Genders, Bodies, Borders (Biddick, 1998); Regulating Borders and Bodies (Molina, 2014); and Border-Bodies (Mbembe, 2023.)

Linh hasn’t read this body of work. He lives across a border from the research enterprise, extramural to our intramural speech. He dislikes the abstractions we forge by travel in our bodies over the university wall out to the field then back in to the seminar. He has heard these words from our lives only when echoed in discourse alone by the professors and students of literature and writing.

I don’t like hearing them from those bodies either.

In the moonlight, he hoisted himself up the funky, kinky hair dangling down the rugged, leaning, tower, trying to tag his dusky reward before the moon struck midnight.

Linh’s sense of the body is at the boundary that maintains homeostasis while ingesting food, excreting waste, communing while defending from other bodies. Most poems in his selection from Borderless Bodies show cell walls straining at these contradictions.

See those on the spread of 2 pages above. Lips are for peeling # Her eyes leak through their shut eyelids # The articulated gas and learnt discharge.

I picked out from among those other leaking peeling articulations the different poem Fairy Tale. The other poems teach me something I already know about multi-cellular life. The prince’s desire mounting dusky Rapunzel’s funky, kinky hair is instead like the poet’s Narcissus and Quang Ngai something new I will remember.

Jam Alerts

The man has got an eye. Two of them! Ambulance means walking and indeed there is a pedestrian. Ambulance means emergency but this one is just gassing up and the walker has her own concerns on her phone.

There was a city so vast, milk could not be delivered from its outlying farms to the center without turning into yoghurt, sometimes cheese, depending on the weather.

Throughout his life and this book the poet has written these brief fables. His contemporary Phan Nhiên Hạo has as well. I like this one.

Some Kind of Cheese Orgy

The biologist, singer, and songwriter, that is, the lyric poet Clifford Cunningham announced to me the first time we met first year of college that his father had introduced individually-wrapped slices of cheese to Latin America. What?

Hilarious. At the time most of us didn’t eat them. We had not yet raised small children. Plastic on slices of subsidized milk evoked what we disliked about our nation. Find Cliff’s song Use Tide! to the same point.

But for others looking in from outside the realm of Indo-European cattle-herders whose chattel became capital itself that photo is the United States of America as in a glass darkly, up against the light.

A spouse can be also be referred to as “my house.” As in: “My house is not home at the moment. Please call back later.” To be married is to live in a new house, to be engulfed by another body.

The collection of cheese slices includes many translations.

Without translation, poetry would be reduced to a few ballads sung by your upstairs neighbor, on his balcony, at 3 AM.

From A Mere Rica includes Viet Nam.

One of history’s oddest ironies is the name Mỹ Lai, which means “half American” in Vietnamese. Mỹ is “American.” Lai is “of mixed race.” If a person is “Mỹ lai” he is half-American. Mỹ in Vietnamese also means beautiful.

Linh selected 1 of his uncollected poems. I have not selected any part of that 1.

After all his selections from his lapsed vocation as poet Linh closes the collection with an interview, an essay, and another interview all speaking from where he is now. Tahseen Alkhateeb first published his interview in Arabic but in London, where it is hard for an Arab or Muslim state to get at you.

Good for him.

Though highly educated, the Unabomber lived in a primitive shack in Montana, away from mainstream society, so by calling myself a Unapoet, I was pointing out my existence away from mainstream America , which in that sentence is depicted as “the long arm of Washington.”

First time I came back from the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, I was fascinated by the fascination of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the New York Times with Ted’s shack. Most of the members of the known generations of my families have at some point lived happily in a shack.

First month I had tried to revive a Vietnamese studies publication at a research university, David Gelertner lost a hand to one of Ted’s packages 1 block away from my office. That same month a Federal agent appeared at my office in a conspiracy investigation suggested by Vladimir Putin to compromise a buddy working at State.

No kidding. Happy to tell you all about it face to face.

My point here is that I regard Linh as the best Americanist ethnographer of my personal acquaintance after my next younger brother his age. But every now and then my friend says something that reminds me well no he isn’t from here is he.

He isn’t, to his credit. It is important to grasp that he came here and he has left. He loves our country like he hates it. In that sense he is very much one of us, shack or not.

My biggest thought crime was penning “Blacks, Jews and You,” in which I discussed racial difference, black crime, Jewish power and, most heretically, mocked the official Holocaust narrative.

Look it up and read it for yourself. “Blacks, Jews and You” is exactly what it sounds like. Not something you write to engage smart people who know what you are talking about. Antagonized.

Too bad. Linh’s attention to those left behind in black American poverty, and the status of those who have escaped, has been for 1 hundred years also a concern of the black American scholarship integral to the freedom movement (viz. Frazier, 1939, 1957.)

His critical view of those who conjure the Holocaust as a unique event of vague import for whatever is also mine, while he has not yet engaged with the exacting historians of the extermination of the Jews of Europe as many specific events of known consequence (viz. Gerlach, 2016.)

The Jews. Oy. Look, I love the guy. I am not going to persecute him, or rescue him from his own thought. Too bad Linh is not Jewish. We could call each other anti-Semites and leave it at that, 2 Jews with 3 opinions about Israel.

It is awkward to consider that a thinker you take seriously has lost his shit. Yet I won’t take his meshugas seriously. Awkward. Well that is life as collected here in Linh’s selections, right?

Born in Saigon, I lived in four different houses. At age 11, I was a refugee, with Guam my first stop, then Arkansas. Settled in the US, I spent at least a year in four different states before entering college. In each of those states, I lived in more than one house. From early on, displacement shaped and informed me. As an adult, I’ve spent at least three months in ten countries, and have visited many more. Almost never driving, I walk, so I can measure each place with my slow moving body. Wandering, you catch more, good and bad.

7 previous Viet Nam letters have addressed the work of Linh Dinh. 4 concern his Postcards from the End of America. The first, on June 11, 2022, judges the book by its cover.

The second, on August 6, 2022, looks at the poet’s postcards from Williston, Wolf Point, the Tri- Cities of Washington, and Portland, Maine.

The third, on August 22, 2022, considers the table of contents of the book and the format of all entries.

The fourth, on on May 11, 2023, considers the poet’s photographs.

That first letter on Postcards from the End of America mentions the author’s views of Jews. So does the second. Another letter, 13 Ways of Looking at a Jew Hater, on April 29, 2023, addresses them directly.

Prompted by my good friend’s work I spelled out my own view in Jews at Viet Nam letters on October 17, 2023. What are friends for?

On June 11, 2014 I revisited my 2010 review of the poet’s novel Love Like Hate for the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, touching once more on his views of black Americans and Jews then drawing attention once again to the beauty of his art.

Viet Nam letters respects the property of others under paragraph 107 of United States Code Title 17. If we asked for permission it wouldn’t be criticism. We explain our fair use at length in the letter of September 12, 2022.

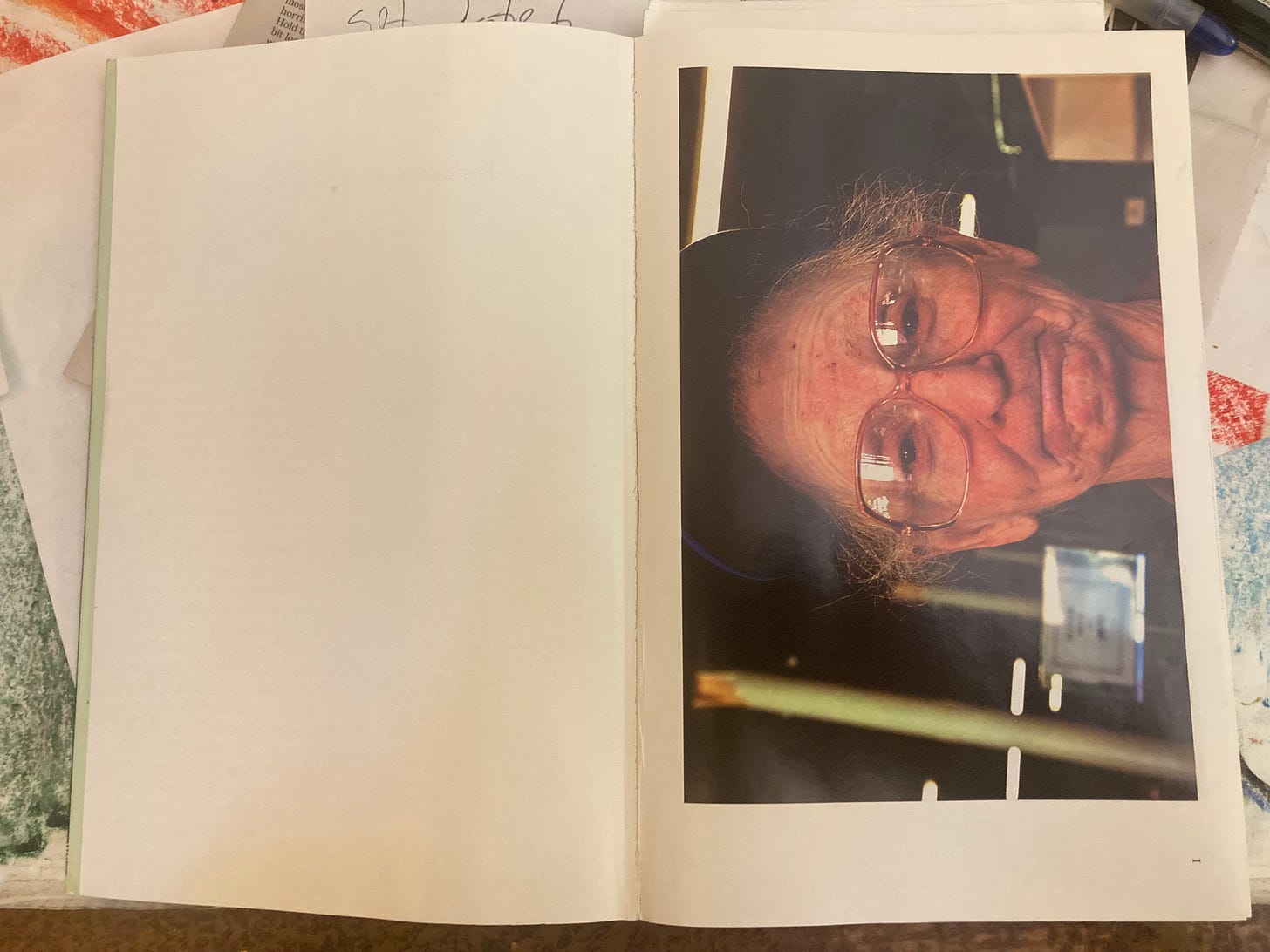

The colophon of these Viet Nam letters, directly above, shows the janitor speaking with poet David A. Willson on a Veterans Day.

I’ve seen that spot you’ve been trying to hide.